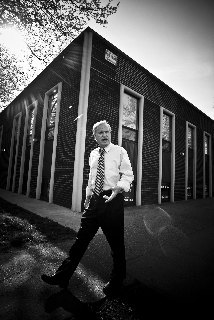

photo by William Hereford

Does long-shot mayoral candidate Tony Avella have a chance? Reid Pillifant takes a look.

Tony Avella notices the photograph of Michael Bloomberg just as he begins to sit down. It is a framed clipping from the New York Sun, trumpeting the mayor’s proletarian tastes, and the headline proclaims this little pizzeria near City Hall: “Where Mayor Bloomberg Goes For Lunch.”

“Oh, perfect,” Avella laughs as he takes a seat. Avella has come here for a quiet talk about his own campaign for mayor and how it might play in Williamsburg and Greenpoint, but, as he well knows, his incumbent opponent casts a long shadow. For the last eight years, Avella has fought in that shadow, as the heretical councilman from northeastern Queens battling the mayor at what seems like every turn, and perpetually castigating his council colleagues for marching in lockstep with the mayor on what Avella says is an agenda of overdevelopment.

Now, he is taking that fight from the council chambers to the five boroughs. Avella’s campaign for mayor hopes to convince voters that—the mayor’s choice of pizzerias notwithstanding—Bloomberg is no common man, and worse, that the billionaire mayor is re-making the city too much in his own affluent image. When he discusses his opponents in the campaign, he is as likely to mention “Mike Bloomberg’s rich developer friends,” as he is his challenger in the Democratic primary, Comptroller William Thompson.

But Avella also has to convince voters that a relatively unknown outer-borough councilman, without much financial support, can somehow defeat an independently wealthy, popular incumbent who is willing to spend unlimited amounts of money to secure a third term.

Bloomberg and Avella were each elected to office in 2001, the Manhattan executive-turned-mayor, and the workaholic activist-turned-councilman from Queens. In the eight years since, the city has rezoned one-sixth of the total land in the five boroughs—more than the last six administrations combined—and the City Council has approved more than 80 total rezonings.

Many of these have been down-zonings, reducing the height of buildings in a given area, but the administration’s penchant for large-scale development projects has engendered a number of bitter fights across the five boroughs—from Atlantic Yards to East Harlem, and from Willets Point to the far West Side.

The City Council, as an unwritten rule, defers to the local council member on these projects, a system that makes most votes nearly unanimous, and often leaves Avella as one of only two regular dissenters (usually paired with Charles Barron, who represents a district in east Brooklyn). Avella’s willingness to reach out to dissenters in other districts has made him something of a pariah among his council colleagues, who recently voted against a minor rezoning in Avella’s district as punishment for his insubordination. “When they act like that they show the childish nature of the leadership of the council,” Avella says of the symbolic vote.

Avella’s outsider status strikes some of his former colleagues as odd. Avella, who currently chairs the Zoning and Franchises Committee, was no stranger to City Hall when he was elected to the council. He had previously served as an aide to City Councilman Peter Vallone, Sr., and to Mayors Ed Koch and David Dinkins. In a recent story in City Hall News, former colleagues suggested the once-promising politician had forgotten everything he learned.

“No, I didn’t forget anything,” Avella says with a laugh. “It’s just that I wasn’t in power with the ability to make decisions,” Avella says. “There are times when you have to speak out to say something is wrong. And if there are other elected officials who feel threatened by that, then there’s something wrong with their positions,” he says.

Avella’s stance has earned him pockets of loyal supporters throughout the city. Robert Doocey, an Avella supporter in Queens, says Avella has been instrumental in fighting over-development in his area, even though Doocey lives outside of Avella’s council district. Doocey recently hosted a fundraiser for Avella and says Avella has helped keep overdevelopment at bay. “There are things that never emerged because you have somebody like Tony Avella in the picture. They take one look and say, ‘I don’t want to spend the million dollars to fight this guy, I’ll just go down the block,’” Doocey says.

Avella insists the issue is universal. “I can bring this subject up in any neighborhood, and people will say, ‘Yeah you’re right,’ because the house over here the building over there,” Avella says, as if pointing out new construction.

It is a message that might be expected to resonate in north Brooklyn, where many long-time residents still express frustration at the 2005 rezoning that opened the Williamsburg waterfront to towering residential developments—and thousands of new residents. “The residents who brought that neighborhood back to make it advantageous for people to move in there are being pushed out of the community,” says Avella.

As mayor, Avella would like to add a paid urban planner to the community boards and then revise the city charter to give the boards more power to effect their own plans for the neighborhood. In Williamsburg and Greenpoint, local residents and civic groups spent months working with Community Board #1 to craft a community-based plan (known as a “197-a” for its section in the city charter), but the plan was simply advisory, and many feel it was essentially ignored by City Hall in the rezoning.

“Unscrupulous developers are getting away with anything and the real estate industry is making money hand over fist,” Avella says. “And that shouldn’t be the case. They shouldn’t be doing the planning. Neighborhoods should be doing the planning.”

But if Williamsburg and Greenpoint are any indication, Avella has yet to gain momentum in the race. In Williamsburg, Avella has raised a little less than $800 on 33 donations, most of which were given in July of last year. In Greenpoint, he has collected just one donation of $50.

“Most people don’t know that I’m running yet, what I am, what I stand for,” he says. He plans to spend the summer speaking “anywhere there’s more than two people,” he says, and believes the steady exposure will give him a boost. “I think if people start hearing me talk about some of the issues and get some media attention those numbers are going to change dramatically,” he says.

Some analysts doubt whether the issue of over-development can sway the large swaths of voters. “In a place like the Upper West Side, [Avella] is not going to take large numbers of liberal Jewish voters away from Bloomberg on the development issue. It’s just not going to happen,” says Joseph Mercurio, an adjunct professor of Campaign Management at New York University, and a veteran political consultant who has worked for both parties.

Mercurio is skeptical that Avella can mount a legitimate challenge to Thompson in the Democratic primary. He says Avella is conceived as “a little bit more conservative, outer borough,” which could hurt him among liberal primary voters. Avella has introduced bills to require foreign-language signs carry an English translation, and has championed allowing nativity scenes to be displayed in schools, alongside holiday icons from other religions.

A Marist poll from mid-May found that 8 percent of primary voters say they will vote for Avella, compared to roughly 30 percent for Thompson and Representative Anthony Weiner, respectively. “The polling that’s out would suggest that Thompson’s the candidate and Avella doesn’t have the fundraising to turn it around,” says Mercurio.

Thompson and Weiner have each raised more than $5 million dollars. That’s seen as a somewhat disappointing figure for Thompson, and it wasn’t even enough to keep Weiner in the race; he suspended his campaign indefinitely in April.

By comparison, as of March, Avella had raised $239,600—a figure just shy of the $300,000 Bloomberg reportedly pays his campaign manager. Between March 11 and May 11, Bloomberg spent $15.7 million dollars from his own vast fortune on his campaign.

Avella bristles at the conclusions that analysts and pundits draw from these numbers. “It is absurd,” Avella says of the millions being raised and spent by his rivals. “If the campaigns just come down to money, then why don’t we just go out and whoever raises the most money is elected and takes office?”’

But money, or the lack of it, is also central to Avella’s campaign. To have any chance of competing, Avella must find a way capitalize on the fact that he is the proverbial David, an underdog who refuses to accept money he views as tainted, such as donations from big developers.

“Nobody’s ever tried to do it without the money,” he admits. “This is a different campaign, and if it succeeds, not only will we reform city government, we’ll send a message that ordinarily people who have a desire to help their community can win high public office without selling their soul to special interests, or the real estate industry, to raise huge amounts of money.”

He admits the numbers make him a long-shot. “But why is that? Not because of policy, or experience or issues, it’s because the political theorists look at it only on the money. That’s the only drawback, that’s the only reason I’m considered a long-shot, because I’m not raising huge amounts of money,” Avella says.

Whether Avella can truly wrap up the Democratic primary, and then challenge a mayor so wealthy that he makes news when he eats cheap pizza, remains to be seen. The answer may lie in his ability to win over areas like Williamsburg and Greenpoint in the three months before the September primary. Avella remains optimistic, in spite of the poll numbers and the dollar figures.

“I think your area will respond very favorably to the issues that I’m campaigning on,” Avella says.

Leave a Reply