An interview with Reverend Billy

By Lucas Kavner

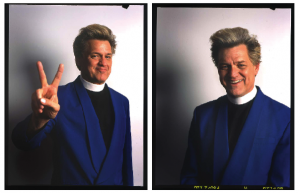

Reverend Billy on his theatrical-activist persona: “This is Gotham City! We create our characters and heroes.” Photos by Brennan Cavanaugh

Preaching a message of anti-consumerism and a return to the bygone days of New York City, is the Reverend Billy (a.k.a. Bill Talen). The reverend and his activist performance group The Church of Stop Shopping, have a history of activism. He has railed and thumped outside the Disney Store in Times Square. He was involved with the Morgan Spurlock-produced documentary “What Would Jesus Buy.” He has a 35-member choir and an eight-piece band. Since the late 90’s the Reverend Billy has positioned himself as a Savonarola against the retail renaissance, pitching hellfire and damnation at the somnambulant mall culture creeping into our vibrant city. Exorcising demons directly from cash registers at Victoria’s Secret. Laying healing hands upon ATM machines. Exhorting midtown tourists not to spend another dime, hallelujah. He is the rev with the big hair. The hipster’s Billy Graham. An icon of New York street life of our times.

And now, the Reverend Billy is running for mayor of New York City on the Green Party ticket. No small honor in this town. In a recent phone interview, the reverend spoke to WG about handing the reins of the city back to its communities.

WG: Can you describe your platform in a few sentences?

REV BILLY: “It’s time for the rise of the fabulous 500 neighborhoods.” That’s one slogan we’ve had for a while. The one we went into battle with last weekend was, “It’s our democracy, stupid.” Democracy is never demonstrated more concretely than in a healthy neighborhood. In a local economy you see the money you’ve spent—you feel it. With the Bloomberg economy, neighborhoods have been under attack for eight years.

What are the first changes you’d make if you were elected?

I’d give lease protection to homeowners and independent shops. Now, when someone says “affordable housing,” we know it’s a con. I would work full time to protect the neighborhoods. Whenever I talk about rezoning and neighborhood planning I say, “Look at what happened to Williamsburg.” People there remember the promises of affordable housing, access to the river, and now it looks like Miami! Those huge high rises, you can’t even find the river, let alone have “river access.”

But doesn’t much of that development conform with the city-approved 197-a plan?

In Williamsburg the plan was very democratic, about mixed-use and protecting people on the ground. But it was ignored! Now we have “the housing of the future”—70- and 80-year-old people being kicked out of their homes, the bulldozers, the endless construction. As mayor I would make sure the social contract was renewed with people. If you invest in your neighborhood, in the flower shop, in the hardware store—you make it a more attractive and safer place to live. The city’s job is to make sure the market is stable enough that you can stay there. If you run a small shop for 70 hours a week and then you have to leave because you can’t afford to live and your shop gets sold to Walgreen’s—that can’t continue. People are rising against the demon monoculture— the sea of identical details flying in from Wall Street.

How would you describe your style of governing? How does it differ from Bloomberg’s?

Right now Bloomberg gets his daily information from these mysterious “professionals.” PlanNYC? Nobody knows who wrote it, and it’s supposed to be the plan for our city’s future. Somewhere in Bloomberg’s forest of teleprompters there are these professionals—you don’t know who they are, and they never talk about neighborhoods. There’s nothing about the day-to-day, raising a family, having a job; it’s all this policy wonky stuff that no one understands.

I would start on the other side—in my body, on the street, with people. I would do what Bloomberg pretends to do in all his million-dollar ads: find the common sense in people living their daily lives, and who have work to do. How much time does it take to get to work, what are you breathing, what kind of energy do you have in your house. This is the kind of stuff you don’t think of in the towers of policy. But when you’re on the ground you take it more seriously.

You’ve said that one of the tenets of your campaign is bridging the gap between the rich and the poor, seeing them mingle in parks together, in their communities. How would you make that happen?

I place a lot of importance on the parks. The parks near wealthier people have been allowed to become private estates of the rich. The poor? Their parks become criminalized. Public space must remain public space. With a progressive tax system we all pay for our parks together, and “rich parks” shouldn’t be glamorous private estates.

The first thing billionaire Republicans like Bloomberg do is say, “We’re broke, our city is broke, so let’s let rich people take care of things.” They’re able to do that by not having a progressive tax system. And, always, one of the first things to go is the park. Parks haven’t recovered from the 1970s, but the ones near wealthy people have these conservancies, these bastard children of Robert Moses taking care of them. The rich and the poor will come together when these public spaces are all financed together once again.

You have a somewhat polarizing public persona—would any aspects of that change if you were elected? Would you balance the artistic side with a political side?

The Reverend Billy costume and the hair and everything—they were made by New York City. They were made in Times Square when Disney started taking over, and Giuliani’s cops were arresting everyone without a credit card. Gradually I grew into the character through the imaginations of the New Yorkers around me, musicians beating on a tin can behind me. I was this televangelist with a different message. This is Gotham City! We create our characters and heroes. At the beginning of the campaign I went to a couple of forums trying to dress like a politician, but I looked like a frumpy professor down on his luck. So I just thought, Reverend Billy is a New York invention and we need some kind of comic book hero right now in the times we’re living in.

How would you subvert some of the things that, in your opinion, Bloomberg has done to mess with the “classic” New York?

Bloomberg’s turning the city into a suburb. Lots of us came here dreaming of realizing possibilities, and it’s all being subverted by his idea that we should be consumers, not citizens. The greatness of New York comes from Charlie Parker and Allen Ginsberg and Tito Puente, these people with a complex humanity around them. The neighborhoods were regarded as necessary, filled with difficult people who don’t fit anywhere in Bloomberg’s New York. We have to rediscover our Charlie Parkers and make sure they stay up with their sax all night long.

If you aren’t elected, do you intend to stay in politics?

I’ve learned a lot running for mayor. We’ve acquired all these musicians and supporters—hundreds of people in the political performance community. This has been a distinct chapter in our work, and we have different adventures that we go on, that take our project in another direction. Our work will never be the same. Goldman Sachs just sold Stella Doro, that bakery up in the Bronx, and hundreds of people are out of work. The mayor should step in there and say, “No, you can’t do that.” I’ll always want to be there for that struggle—to step up for a community like Stella Doro. That’s what matters most to me.

Leave a Reply