NORMAN MOONEY, “WALL FLOWERS”

NORMAN MOONEY, “WALL FLOWERS”

Causey Contemporary 92 Wythe Ave., through 4/13

Causey Contemporary unveiled its vast new location with Norman Mooney’s show of five geometric sculptures that combine industrial brawniness with floral daintiness. Three freestanding constructions called “Windseeds” resemble white pollen grains from a distance and appear as though a gentle gust would send them tumbling toward McCarren Park. Up close, however, their sharp aluminum projections make you fear for your safety. All the sculptures, in fact, elicit this anxiety; touch them the wrong way and you will bleed.

“Wall Flower No.1,” a starburst of yellow aluminum blades, allures you toward its core like a thirsty bumblebee before you jump back from its snarl of prickly metal. The dark-red “Wall Flower No. 2” seems somewhat less menacing simply by the nature of its material: translucent resin. In this piece, Mooney has arranged the projections in a more intricate pattern, jutting out from the center then receding at the periphery. This creates an optical illusion in which the spikes at the edges appear to wiggle as you stare at the midpoint. Simplicity of form belies complex emotional power in Mooney’s sculptures—danger and delicacy coexist harmoniously and manufactured materials imitate natural wonders.

EMMELINE DE MOOIJ, “MUDDY”

Capricious Space 103 Broadway, through 4/17

Dutch artist Emmeline de Mooij likes to get dirty. In past works and performances, she has spent several days naked in the woods and built nests in indoor spaces. For “Muddy,” which is also the title of her new book, de Mooij explores the caves of her psyche, where she uncovers the most primitive aspect of her being. This primitivism is best expressed through stone-like wall sculptures of chunky masks that look as though they were uncovered in an archaeological dig. These masks are so exquisitely crude, with bulging eyes and gnarled mouths, that they make Picasso’s paintings of African masks look downright civilized. The sculptures hang in front of enlarged vintage photographs of intellectuals engaged in conversation. Like mischievous poltergeists, the masks add a precocious humor to the pictures.

There’s something of a nutty prophet inside de Mooij. She portends in her artist’s statement that “the era of unexpected growth of gravity has come.” (That’s an idea that will make your bones ache at night.) And the sculpture-print combinations in the show do carry a heavy load, both visually and conceptually. The mind of this artist is a wondrously haunted excavation site.

COLBY BIRD, “KNOLL SOFA”,

Real Fine Arts 673 Meeker Ave., through 4/11

Encountering Colby Bird’s installation feels a lot like stumbling into an abandoned office space: your footsteps echo off the bare walls and the only object in sight is a tattered gray sofa, too soiled and torn to sell on eBay, situated in the center of the room. This piece of furniture was once something special—a sleek Florence Knoll Sofa, symbol of mid-century American modernism—before it succumbed to the ravages of time and neglect. Now it serves as a wisecrack on the ridiculousness of the art market and the piece’s own loss of desirability. But perhaps the old sofa has regained some its former glory, this time as a unique work of art rather than a functional product. Who am I kidding? It’s just a trashy couch masquerading as art. But I guess that’s the point.

BRIAN CONLEY, “MINIATURE WAR IN IRAQ…AND NOW AFGHANISTAN”, The Boiler, 191 No. 14th St., through 3/21

Snipers hold their positions on rooftops; a puff of smoke, like an unfurled cotton ball, billows from an exploded vehicle; a U.S. helicopter crashes in the dunes on the outskirts of town. No, this is not a preview for the next war-porn movie. It is the remnants “Miniature War in Iraq…and now Afghanistan,” a scaled-down model of a battle in Iraq that was played out by gamers working under the direction of artist Brian Conley. A large screen projects the gamers in action, tipping over tiny fighters as they die. (The gamers, apparently, really got into the headspace of their warriors, a psychological zone they called the “magic circle.”) Other monitors show the websites and news programs that researchers, fluent in Arabic, used as real-time source material. In the end, though, the gamers relied on Conley’s rulebook and a literal “roll of the dice” to gain a final outcome in the battle.

To be honest, the rules of the game will bewilder the layperson, but the sculptural end product has a charm all its own. And the act of combining real, potentially horrific, events with a game is an interesting commentary on the concept of truth. It may sound counterintuitive, but this little panorama of toy soldiers brings home the war in a more visceral way than even live news footage can achieve. Maybe it’s the fact that mundane details of the battlefield are in full view. Or it could be that art is sometimes realer than reality.

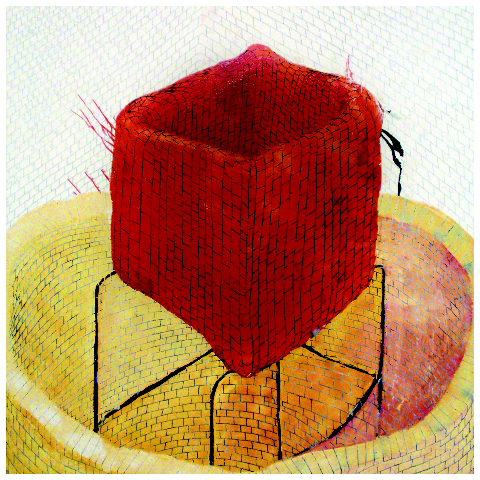

ANDY PIEDILATO, “NEW PAINTINGS”

English Kills Art Gallery, 114 Forrest St., through 3/21

Bricks, normally thought of as dull and reliable building blocks, behave preternaturally in Andy Piedilato’s latest exhibition of gigantic square paintings. Undulating and serpentine, masonry was not meant to be this curvaceous, but there it is, oozing sensuality and moving in obstreperous patterns. It’s easy to guess where Piedilato might have found his inspiration. One needn’t look farther than the vast factories and warehouses that neighbor his Bushwick studio. “Orange Cube” shows a cuboidal water tower-like structure inside the maw of a yellow chimney bound by creamy walls—a cup in a tube in a box—like some post-industrial Russian doll.

In much of his past work, some of which is only display here, Piedilato has spilled paint across his canvases in an indiscreet manner. His new works employ much more cohesive splatter techniques. Gentle whisks and splotches serve the piece as a whole and not just themselves. The best example of the artist blending painterly methods shows a brick ship (an oxymoron indeed!) getting attacked by a sea monster as Action Painteresque waves crash against the hull. In this painting, Piedilato has found a way to integrate geometric precision and messy passion.

JOHN PLUNKETT, “THE ABSURD LIFE” Gitana Rosa Gallery, 19 Hope St., through 4/3

Taking its title from the celebrity-reality TV show “The Surreal Life,” this exhibition of paintings places funky automatons in stark white environs. The figures often adopt poses from famous art-historical works but with a heavy dose of zaniness. “Boys Night Out,” John Plunkett’s version of “The Last Supper,” shows a Christ composed of ball-and-socket joints, hosting buddies made up of metamorphic rock, metal pipes, bunny ears, luscious lips, and giant eyeballs. Through the windows lies a rocky landscape straight out of a Salvador Dalí painting, a nod to the artist’s Surrealist forebears.

Plunkett’s hallucinogenic hybrids are impeccably drawn: shiny, robust, ultra bright, and in defiance of the laws of nature. We want to relate to them—in many ways they behave exactly like people—but they are so damn strange. Only in one piece do we see what can be identified as human. In “A Genius Is Born,” a japonisme style baby squats in a white cube, its hands in a defensive posture. Mechanical creatures stare at the infant through doors and a window, mesmerized by the freak of nature. The creatures are us, cruel and social and insatiably curious.

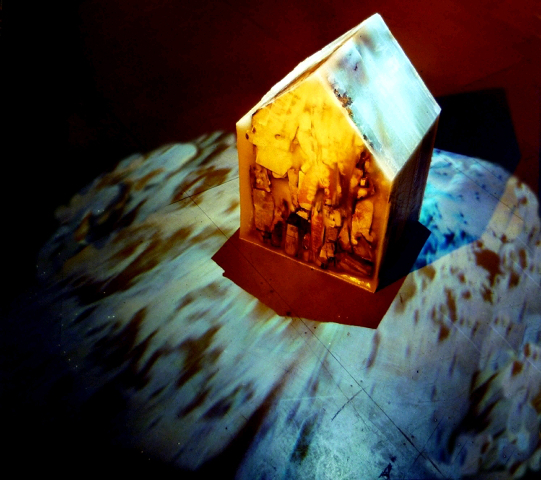

RON ROCCO, “SHAKE UP!”

(CTS) creative thriftshop @ Dam, Stuhltrager Gallery, 38 Marcy Ave., through 3/19

“Shake Up!” is about as mixed as a mixed-media installation can be while still attaining a sense of restraint. Audio, video, photography, ink, fabric, wax, and trash are all neatly incorporated into one cerebral sculpture. A dense thigh-high house, created from compacted garbage that has been sealed in wax, serves as the central motif in Ron Rocco’s installation. Directly onto the house, a projector shines footage of a tree with scant leaves blowing in the wind, as the sound of an encroaching thunderstorm booms ominously. A long sheet of fabric covered in inky tire marks surrounds the structure like a sinister highway.

As a whole, the installation touches on multiple environmental issues: the wastefulness of conspicuous consumption, the encroachment of automobiles on natural habitats. And though Rocco conceived the piece in 1997, its iconic centerpiece—the house—has perhaps taken on new significance, as an emblem of the housing-market collapse. A fine example of how a symbol can change in the viewer’s mind over time.

Leave a Reply