Patrick O'Hare's "Sam's Club, Waterbury Connecticut,"2004. C-Print on Fuji Crystal Archival Paper, 20 x 24"

The human body as a subject in art tells us as much about our society as anything intended by the artist. Even representations of the inner workings of the body reflect social beliefs and cultural perspectives. The ancient Chinese, for example, had no tradition of autopsy and as a result had no clear mapping of the internal organs. Despite this, they were able to develop a sophisticated system of medicine based on the outward signs of inward disease.

Today’s dominant perspective on the human body is a systems approach (circulatory system, central nervous system, etc.). This can be interpreted as an expression of the way we educate and organize physicians professionally rather than an empirical truth.

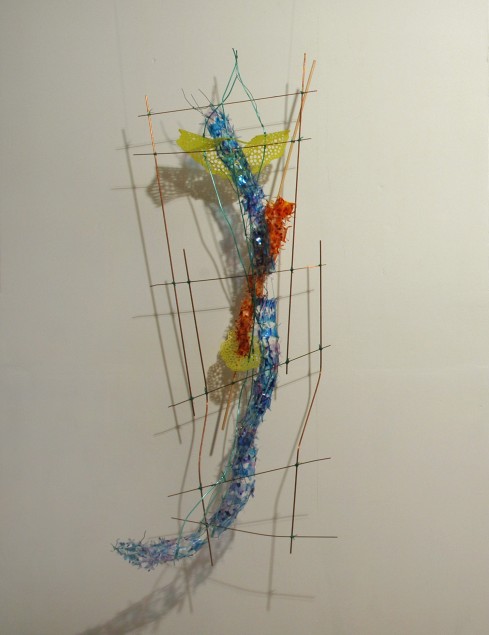

Margie Neuhaus' Fragment I. (2010) Copper coated steel, ink on mylar, vinyl coated wire, thread, plastic coated wire, acrylic, 42 x 18 x 20 inches

Margie Neuhaus’ ephemeral and buoyant constructions mimic the organic plumbing of the human body but the overall effect is closer to medical illustration than to a cadaver. Neuhaus’ hanging constructions are extremely light and seem magically suspended in space, similar to a hologram, an effect made more pronounced by the bright, translucent materials. They invite movement and one even wants to put a finger through the highly charged negative spaces.

All this results in a high degree of mental abstraction—in this case in the form of a highly refined aesthetic. Complimenting the sculpture, are a series of layered, translucent works on vellum. Much in the same spirit, they reproduce details of the nervous and circulatory systems, and like the three-dimensional work, they too leverage light and transparency to produce a glowing, charged effect.

As the inward conception of the body is the subject for Neuhaus’ work, O’Hare turns his gaze outward to the landscape—not as an examination of nature or society but as a mediated landscape that lies somewhere in-between. His subjects hang in the balance between the forces of industrial development and the regenerative power of the earth. O’Hare’s work takes the long view, making no distinction between successful industry and failed, forgotten remains.

With industry’s impact on the landscape as a subject, it would be easy to take a few obvious shots at the demon, but O’Hare’s photos are more complex and equivocal. They remind us that fortuitous accidents (are they miracles?) can happen anywhere—even on the backside of a corrugated metal warehouse.

They also suggest that nature, despite the abuse we throw at her, is resilient enough to demonstrate beauty and civility even after the civil engineers have their way with her.

Another theme in O’Hare’s work is an exploration of atmosphere—especially when it is thick with smoke, rain or particulates. Similar to his industrial images, these find beauty and mystery in the unexpected: The rain storm that one wants to get out of, or the acrid plume from a garbage fire.

While the prints included in this exhibit were the perfect scale for the venue, I can’t help but wonder how these images would look at a larger, more enveloping scale.

{Gg Gallery} 119 India Street, Brooklyn, NY 11222

MAY 15 – JUNE 13, 2010

Meet the artists on Sat, June 12, 5-8pm

By Robert Egert

Leave a Reply