photos by Benjamin Lovosky

The original breaking news, investigative reporting on this story was first done by Benjamin Lozovsky, and followed quickly by stories appearing in several other New York City newspapers.

In the next few days, the City Council of New York City will hold a final vote that determines the fate of the old Domino Sugar factory, a massive 19th century industrial site along the Williamsburg waterfront. The for-profit developers CPC Resources (CPCR) have campaigned long and hard, spending close to three million dollars on lobbying efforts, to win the community residents and politicians over to their high rise luxury housing proposal, on the promise of 660 affordable units, open space accessibility to the waterfront, and jobs. Approval of the plan would rezone the site from heavy industrial use to mixed-use (residential/commercial), and would allow the developers to build towers up to 34 stories high.

As the New Domino proposal moves towards the final vote by the City Council, some long speculated and critical details of the plan have finally reached the surface of what so far has been a murky evaluation process. Despite CPCR giving their word that they will be legally bound to their promises regarding key aspects of their proposal, including the affordable housing and permanently affordable home ownership components, it’s not reflected in the documents the City Council is to vote on.

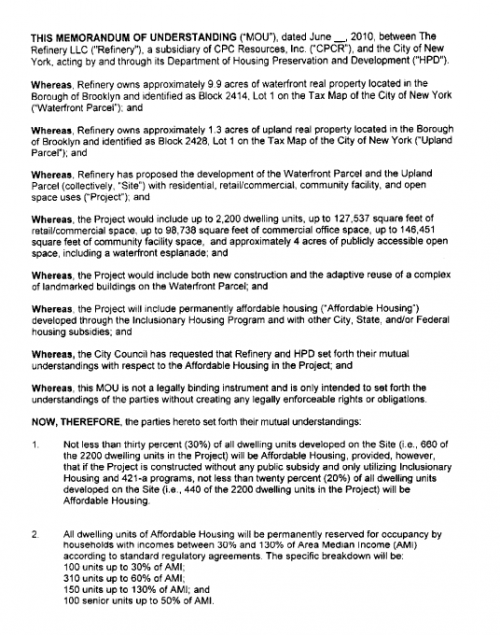

Unlike the Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning of 2005, which spelled out the inclusionary housing goals and benefits in the zoning text, the affordability aspects within the New Domino proposal are in a separate letter, a non legally binding document called a memorandum of understanding (MOU).

Photos were taken in early June at an Anti-Domino Rally and City Council subcommittee meeting and hearing. Council Members Stephen Levin (at far left) and Diana Reyna (at far right).

When Council Member Stephen Levin, who worked to get the height and density reduced on the project, spoke with WG News + Arts, recently, about how the affordability would be enforced, he says, “We’re talking about not only the height, but the affordability requirements, all of that is written into the rezoning. For instance, 30% percent is required whoever the developer is. That carries through with the land.”

But it seems what will end up happening is different than what the council member envisions. While technically a MOU can be legal document, in reality it holds a flimsy standpoint in the eyes of the law.

Tom Angotti, a professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY says that such side agreements that take the form of a memorandum of understanding, are “of questionable value and legality, and there have been instances in which MOUs have been signed, and there’s no follow-through or enforcement.”

Angotti attributes the fact that MOUs play little part in any decision making process because they’re not part of the public discussion.

“Well, first of all [MOUs] are not part of the land use review process, so it’s entirely outside the decision-making process,” Angotti says. “They can be negotiated behind closed doors, the mayor can sign it, but that doesn’t necessarily obligate the city to do anything. In fact, they are very often couched in legalese that leaves the city an out.”

In the case of the New Domino plan, the “out” lies not just with the city but with the developer CPCR as well. From a copy of the actual MOU (see at end of article) for the proposed New Domino plan, exclusively obtained by WG News + Arts, paragraph 9 in the text clearly states:

“Whereas, this MOU is not a legally binding instrument and is only intended to set forth the understandings of the parties without creating any legally enforceable rights or obligations.”

If it sounds too good to be true, remember that in other famous MOUs that have so far not been fully met, if at all met, like the second MOU attached to the Atlantic Yards proposal, developers were actually required to pay fines and restitution if the deal were to fall apart. In this case, when the deal fell apart, neither fines nor 30-day notice of termination of the agreement are included.

Surely politicians could have seen this coming, given all the red flags surrounding previous uses of MOUs. Even the new City Comptroller John Liu encountered problems during his time as the Council Member for the 20th District in Queens.

(At left) President and CEO of CPC Resources Michael Lappin, and at microphone Vice President of CPC Resources Susan Pollock.

During Liu’s term as a council member, he negotiated an agreement with the Mayor’s office regarding a land use proposal in his district. At the time, Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff signed a MOU and issued a letter committing the to city certain conditions for the Flushing Commons Project. Things changed when Doctoroff left office. “Doctoroff is gone, the city changed its mind, the mayor’s office changed its mind, and the MOU goes out the window,” Angotti says, “and there’s really nothing anybody can do about it.”

The struggle to enforce agreed upon promises must have hit home with the then council member because shortly after he was elected City Comptroller, earlier this year, one of his first orders of business was launching a task force, The Comptroller’s Task Force on Public Benefit Agreements, to investigate how these type of agreements are used to gain support for projects and then are not enforced.

“Where does the buck stop?” comptroller press officer Scott Sieber says. “There are questionable processes in place.”

All of the countless meetings, presentations over a period of five to six years appear to be meaningless given the documents that have been made public to date—and the use of a MOU to make the promises. In fact, in the MOU it mentions that the developer can simply choose to only create the standard 20% affordable units if they choose to not take the public subsidies, far below what was promised, and it would be within the allowance of the agreement. Also, there is no mention of the 100 permanently affordable homeownership units very often mentioned as a basic part of the plan given forth by CPCR. Whether this has been written into the zoning text is unknown, but unlikely.

Furthermore, there will be no restrictive deeds or clauses attached to the zoning that could act as an arm of enforcement in case the proposal failed to meet its stated objectives.

Promises and Trust

So now the great debate about permanent affordable housing on the Southside Williamsburg waterfront has been distilled down to two things, promises and trust.

The trust comes in the form of open and welcoming arms and prayers of the Southside residents who count on their community leaders, both those of faith and political, to guide them. The guidance some of the community got was to trust the developer CPCR, the for-profit development arm of a not for profit lender for affordable housing projects and their partner Isaac Katan, a for-profit developer, to live up to the many promises they made during the rezoning review process.

So far, the reaction has been one of faith.

“I totally understand how people may feel. All you have to do is look at that Lower Manhattan project which is now market rate housing,” says El Puente President Luis Garden Acosta, acknowledging that many of these deals undermine the community’s trust and don’t come to pass.

He was referring to a case in the 1980s when a generous amount of affordable housing was promised around the Financial District but never materialized. Acosta remembers the woes of the city after that failed attempt.

“And then when you look at it, and it hasn’t happened,” Acosta says, “then people have a right to be skeptical about the promises that have been made in regards to affordable housing.”

Ultimately, Acosta is unwavering in his support of the project. “We take them at their word.”

Father Rick Beuther, parish priest at Sts. Peter and Paul Parish, is even more succinct with his faith. “We trust them,” Beuther says. “That’s my comment.”

Acosta is a tad more pragmatic than the father though. Discussing the potential for CPCR to change their intentions he alludes to what might happen if CPCR “totally moved to the dark side, so to speak,” and become “a conglomerate of greedy profiteers, who really are about using and abusing communities rather than supporting and empowering them,” Acosta says.

In that case, Acosta plans on standing up for his community with the same passion he has applied over many years throughout the Southside.

As far as CPCR staff, Acosta says, “When I tell you that I think Susan Pollock [senior vice president of CPCR] is a woman of integrity, and that she will stand for what has to happen, I can see her, if this is not going correctly, she will be the first one to resign.”

“The people will demand that they keep their word, should they ever veer off course,” Acosta says.

On the political front, there’s Council Member Diana Reyna, who represents the inland district neighboring the New Domino site. She became an ardent supporter and jumped on board when “they [CPCR] upped their offer of affordable housing to 660 units, and then offered affordable home ownership,” Reyna’s deputy chief of staff Bennett Baruch says. Even with the news that none of the deal breaking decisions for Reyna are set in stone, the Council Member is still fully behind the development reports Baruch.

Former land use committee chair of Community Board #1 Ward Dennis’ response regarding this latest development regarding Domino: “If that’s the case, then that’s not a good thing. Obviously what we as a community want is something that is legally binding not only on this owner but on any future owners, so that what is built, is what was promised,” Dennis says. “That’s exactly why the community board was pushing so hard to get as many of those agreements in writing, hopefully there’s more that does make it enforceable.”

There does not appear to be a restrictive deed that incorporates these promises as part of the rezoning, which is a legally binding document. So the project comes full circle: a massive over development, a 25 year tax abatement and no level of enforcement for which Dennis and his fellow community board members had rallied so vehemently.

Leave a Reply