WINDOW CAKE WITH DECORATIVE DOLL FROM LA VILLITA BAKERY.

Life in New York City can be so over-stimulating that it’s easy to overlook the civic details we encounter every day. Take, for instance, the MetroCard. You can immediately identify it in your wallet as the yellow rectangle of flimsy plastic with blue lettering. But you may not know (or remember) that the colors on the original MetroCard were reversed—yellow letters on a blue field. These are the kind of arcane factoids that titillate the folks at the City Reliquary Museum and Civic Organization, who proudly display a blue MetroCard from 1994 next to myriad old subway tokens.

Located between a bar and a pizzeria at 370 Metropolitan Avenue, with a yellow awning overhead, the outside of the City Reliquary looks more like a neighborhood bodega than a museum of New York artifacts. Inside, however, past the ka-chunk-chunk of an antique turnstile, the space reveals itself to be a curiosity cabinet on a shop-size scale.

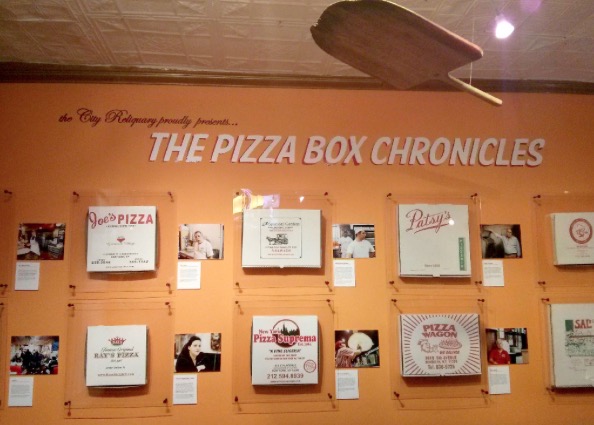

Nearly every inch of wall in the main exhibition room contains some piece of New Yorkiana. There’s a shrine to Jackie Robinson, composed of baseball cards and black-and-white photographs clustered around a folk-art painting of the legendary Brooklyn Dodger. A mysterious locker promises to divulge a “Brief History of Burlesque in New York.” A grid of Statue of Liberty postcards covers a whole wall near a case of Lady Liberty figurines, one dressed in a hula skirt. Other displays feature 1939 World’s Fair paraphernalia; seltzer bottles made in Brooklyn; “grab holds” from the transit system; a reassembled newsstand from Lower Manhattan; chunks of native metamorphic rock; architectural fragments from the Waldorf Astoria, the Ritz-Carlton, Grand Central Station, and the Flatiron Building; and, of course, an assortment of New York exo-numia. “Exonumia are non-currency coins,” such as the afore-mentioned subway tokens, explains Dave Herman, president and founder of the City Reliquary.

At first sight, Herman is not the kind of person you would expect to find running a museum of old-timey doodads. He’s a tall, semi-athletic guy with clean-cut brown hair who, at 34 is much younger than many of the items he collects. He is also a firefighter based at the firehouse on nearby South 2nd Street—Engine 221, Ladder 104.

Originally from Florida, Herman moved to Williamsburg in 2000 after completing a master’s degree in fine arts at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. For a while he made sculptural and installation work but grew tired of the insular art world. “I was always interested in doing things more in the public realm than in a gallery,” he says. “So I signed up for the fire department and started the museum.”

The combination serves him well. Here is how it happened. In 2002, Herman began placing local artifacts in the window of his ground-floor apartment at the corner of Grand and Havemeyer streets—and the City Reliquary was born. Soon, the windowsill museum began showing the collections of other people in the community, complete with receptions on the sidewalk. Herman and likeminded collectors formed a board of directors to gain nonprofit status, and in 2006 the City Reliquary moved to its present-day digs. They funded the museum largely through small donations, memberships, and benefit events, which has been their survival strategy ever since.

Today, the original window exists as a sort of time capsule. Dust has settled on the artifacts, and a pushbutton audio tour has fallen silent. “Since we moved into the mu-seum, that window hasn’t been touched,” Herman says. “It’s becoming what inspired it—other types of curious displays and landmarks of the city that were unknown or underappreciated.”

In addition to its permanent collection, the museum hosts rotating exhibits in a back room, where you will currently find “Forgotten City Lights,” curated by Kevin Walsh, webmaster of Forgotten-NY.com. The show chronicles New York City lamppost designs through a multitude of photographs taken by Robert Mulero, an MTA employee who, for over 30 years, has documented old streetlamps before they are replaced with newer models.

Though the show lacks some cohesion—with mismatching picture frames and a scattershot layout—it offers gems of insight into how the city’s lights have evolved over the years. A timeline on one wall highlights key points in lamppost design, from the heavily adorned wrought-iron posts of the early days of electricity to the no-nonsense aluminum posts of recent decades. (Interestingly, the year 1980 seems to have spawned a resurgence of decorative streetlamp styling.) Also included are a few elegant draw-ings of lampposts by Mulero that almost outshine his matter-of-fact photographs.

“Forgotten City Lights” quietly embodies the City Reliquary’s ideals of civic pride, historical inquiry, and spotlighting ignored objects. One of the museum’s chief ambitions has been to acquaint Brooklyn newcomers—hipsters, urban professionals, et al.—with the history of their surroundings. “Many people who were coming to the neighborhood, maybe for lack of interest or desire, hadn’t been paying attention to what came before them as they were transplanted here,” Herman recalls. “So I thought it would be nice to create a space where a dialog could be created, where people could have a reason to stop and learn a little something about New York.”

“Forgotten City Lights” quietly embodies the City Reliquary’s ideals of civic pride, historical inquiry, and spotlighting ignored objects. One of the museum’s chief ambitions has been to acquaint Brooklyn newcomers—hipsters, urban professionals, et al.—with the history of their surroundings. “Many people who were coming to the neighborhood, maybe for lack of interest or desire, hadn’t been paying attention to what came before them as they were transplanted here,” Herman recalls. “So I thought it would be nice to create a space where a dialog could be created, where people could have a reason to stop and learn a little something about New York.”

“Forgotten City Lights” is on view at the City Reliquary through early October.

370 Metropolitan Avenue (@ Havemeyer Street)

Sat & Sun (12am–6pm); Thurs (7pm–10pm).

Weekdays by appointment (718) 782-4842.

Free. (Donations accepted.)

Leave a Reply