Marieke Wegener (in her Williamsburg studio) began interviewing many area artists this summer for her documentary about the artist Mark Lombardi who allegedly died of suicide in 2000. Photography by Ben Lozovsky

Mareike Wegener is a 27-year-old German filmmaker with spot-on taste for the obscure, the quirky, the hard to pin down—particularly when it comes to visual artists. What’s more, she’s got a sweetly fierce determination to follow her instincts to their fascinating, if open-ended, conclusions. While in school in Cologne, Germany, Wegener managed, over the course of four years, to fund and produce a film on the late Al Hansen (wandering conceptual artist extraordinaire, member of the transgressive art movement Fluxus, and otherwise known as Beck’s grandfather). Now she’s hard at work on an even edgier project, but one much closer to home: a documentary on the late, great artist Mark Lombardi, who died at the young age of 49 (suicide) in his Williamsburg studio in 1999. Local gallery, Pierogi, handles his estate: epic drawings that are, at first glance, little more than diagrams in pencil on paper, but which ultimately claim to chart the scandal-riddled courses and interconnected destinies of political movements, presidents past and seated, political parties, world banks, and, most frightening of all, terrorism. Controversy has followed the work since Lombardi’s death, and the FBI is even rumored to have closely scanned one work in particular in the wake of the events of 9/11. Wegener, meantime, is spending the better part of this and last year sorting out the legacy and history of Lombardi, the man—a task that no filmmaker, until now, has dared to take on for its complexity. It’s a project that’s made her a de-facto W’burg resident.

Late mornings you can find her smoking hand-rolled cigarettes on Bedford Avenue, drinking lots and lots of coffee. Jittery, but better for it, we did the same. What ensued was a conversation that, much like a Lombardi drawing, was full of fragments of interconnected lives, open-ended answers, and some beautiful insights into what makes the creative mind tick.

Give us some brief background about yourself.

I was born in North Rhein Westphalia, in a small town close to the Dutch border. My dad had a jazz bar, so I grew up with jazz musicians…beers. I moved to Cologne to study when I was 20, but I knew I wanted to make films since I was 16. I applied to an art school, the Academy of Media Arts, that had a strong film department, but I went first into the Drawings Department, then sneaked into the Film Studies Department.

Do you think your experience with drawing helped guide you to Lombardi?

Definitely. I’m appreciative of people who draw, where I can see their craft. In Lombardi’s case, seeing the “hand” that is presenting the information to us is important. If he had done computer generated images, which he could have done, you wouldn’t feel the pain that goes into drawing things like that for hours and hours. You need to understand that someone spent time with it. The research is, of course, another level of his time-consuming, obsessive work.

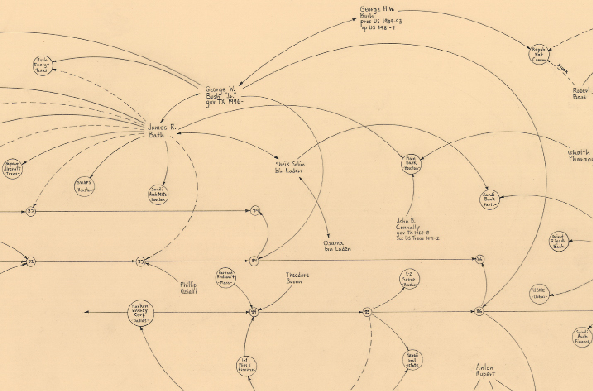

Detail of drawing by Mark Lombardi, “George W. Bush, Harken Energy, and Jackson Stephens, ca. 1979-90” (5th version), 1999, 24×48 in. (an example of how the artist mapped criminal corporate-government connections.) Private collection.

Why make a film about a character as difficult to grasp as Lombardi and why now?

At first I didn’t want to make another film about an artist that isn’t around anymore. I’d known about Lombardi’s work for about 6 years, but it wasn’t until the financial crisis that I knew I needed to do this project for sure. I felt that with everything that is going on right now, that people would be intrigued. His work touches so many things that have to do with the real world.

Tell us about what being a filmmaker in Brooklyn is like, day to day.

During the preproduction, I have to do a lot of boring stuff: calling people and scheduling things, making appointments. But once we start shooting, it gets really exciting. Getting to know all these interesting people that I interview, and going to places I would never have access to if it weren’t for the film, is a great thing.

What do you feel both your subjects, Hansen and Lombardi, have in common?

What I like about both of them is their level of professionalism, of not making any compromise when it comes to their work. I think that’s fascinating, though their subject matter is so different. The one, Al Hansen, deconstructed systems, while Lombardi seems to be the opposite, showing and depicting systems that we might not see. I think Hansen had a clear understanding of the worlds and system he lived in too, but he had a very different reaction. His was a reaction born out of his time.

What time was that?

The times that Hansen lived in, the ‘60s and ‘70s, were a good time to break up the things that already existed. But I guess that the time we live in now…things are not so clear and visible for us; there’s more confusion, and it makes sense for us to want to try to find ways to navigate through it.

Tell us about how you first came to Williamsburg. I’m based in Cologne. The first time I came to New York was in 2003 while I was still in school. We had an exchange program with Rutgers University, in New Jersey. We went out to see galleries in Chelsea and whatnot, and at some point our professor took us to Brooklyn, and the first gallery we went to was Pierogi. They were installing an exhibition at the time, and I remember being struck by the friendly and informal atmosphere there, which was such a contrast to what I’d seen in Chelsea. Ever since then I kept coming back to Pierogi to see what they had up. Now I am working a lot with Joe and Susan [Pierogi’s gallerists] on this project, and they are very helpful.

Can you name one particularly controversial work of Lombardi’s, and tell us about the effect it’s had on the public?

The BCCI Drawing [“BCCI-ICIC & FAB, 1972-91”], the big one, which is owned by the Whitney, was examined by the FBI after 9/11. It shows the connection between Western banks and Middle Eastern banks, U.S. and European politics, war and terrorism—it’s practically showing the place of the globalized world, the people who have influence through politics and finance. It has over 300 names in it. It’s huge; and has so many side plots. [Art historian] Robert Hobbs, in his essay for the catalogue for “Global Networks”—a show that traveled to nine national museums—says Lombardi’s drawings are actually like history painting, only in a conceptual way. So in 200 years, when people look back at Lombardi’s drawings, they will clearly see our time, our era. Personally, I think the way Lombardi treats information says a lot about our time, and people’s current fascination with information. We need to process all the information we get, every day, and we can’t; and here he is, making a drawing, a visual map, of these things, as if he can explain everything to us in one drawing.

What do you think about all this controversial information in the work? Was Lombardi, as it were, “right”? Or does verifying his facts matter to you at all in this film?

I looked at news material on the BCCI Scandal to see how he filtered the information down, and how he made it abstract again. I’ve also seen his index cards. He had 14,000 of them, where he wrote down the names of people in banks, politics…little notes that he distilled from books and newspapers. Some people who knew him claim that right away, he could just look at these cards and make all the connections in his brain. Then he would lay out the cards, and that would lead to the drawings. As for whether he was “right” or not, I think it’s important for me to believe he’s right for the sake of the film, but it doesn’t matter to me one way or another, if one name is wrong or whatever—even though he would freak out if one name is wrong. What’s more important is the fact that he, as an artist and researcher, felt he needed to get it right. I think he saw himself as both artist and researcher and that both were, on balance, of equal importance.

Name some of the people that we associate with the Williamsburg art scene whom you’ve interviewed.

Greg Stone, Fred Tomaselli, Joe Amrhein and Susan Swenson, James Siena, Raphael Vargas-Suarez—the latter was the only one who had photos of Lombardi. I would ask simple things of people like “what kind of music did he listen to?” Simple things, but almost nobody had the answers. Most could talk about the work, the scene, but nobody could talk about what was going on inside of him. I went to visit his family in Syracuse, and one of his sisters said, “How well do you [ever] know your brother?”

So who really knew Lombardi?

Nobody.

Are you making a film about an enigma?

Yes. But I think this could be one of the qualities of the film. On the other hand, I feel challenged to create a personal look at him, because that’s what interests me as a filmmaker.

How are you going to manage that?

Even though it’s so difficult to grasp him as a person, there are still fragments. I’m not after the “whole truth” about a person I didn’t know. I don’t have the authority to say. But I can build an atmosphere that is connected to, and shows, that person. I can show him in the relations he had to other people and through his ideas and thoughts.

The film (not titled yet) will have a theatrical release in Germany in the spring of 2011, and will be premiered in New York sometime soon after. A television version is also planned to be broadcast on ARTE, a German-French cultural program.

The film is produced by unafilm, based in Berlin and Cologne, co-produced by ARTE Television, and funded by numerous German film funds, including Filmstiftung NRW, Ministry for Culture and Media (BKM), and the German Federal Film Fund (FFA).

Leave a Reply