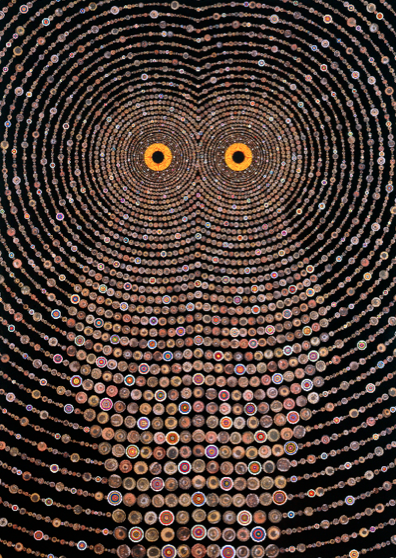

“Echo, Wow and Flutter,” 2000.Leaves, pills, photocollage, acrylic, resin on wood panel 84 × 120 inches. Copyright the artist Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

I first met Fred Tomaselli in the early 1990s, after he moved to Brooklyn from the West Coast and established a studio in Williamsburg. Word was out about his densely crafted paintings with psychotropic drugs embedded in resin. Flash forward to a hot summer evening in 2010, when Tomaselli took time to discuss his work, its influences, and his mid-career survey at the Brooklyn Museum.

I met Tomaselli in his second-floor studio, where the walls were hung with paintings ranging from finished ones completed in the early 1990s to a piece still in-progress. On a work table nearby sat a scale model of the Brooklyn Museum exhibition space, with postage stamp sized repro ductions of his paintings.

Tomaselli has a highly developed style that is unique enough to be immediately recognizable, yet broad enough to accommodate his diverse and fluid interests. His paintings use pills, leaves, and found images encapsulated behind a thick layer of resin, but his references go way beyond the specific materials. A closer look at his work reads like an encyclopedia of scientific, medical, and social topics. Viewed at once, as we have the opportunity to do at the Brooklyn Museum survey, we can see his ability to use his method of making art to synthesize ideas from diverse disciplines and cultures.

Among Tomaselli’s antecedents are the obvious ones, such as Renaissance painter Arcimboldo, (best known for his anthropomorphic still life paintings where a multitude of fruits, vegetables, books or flowers combine to resemble human portraits), or Buddhist devotional images known as thangka, which prefigure the dense but shallow space of Tomaselli’s work. Less obvious are the contemporary influences such as 1960s op-art artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Victor Vasarely, whose shimmering surfaces are always in tension with the three-dimensional, illusionary space they produce. Among his contemporaries, it is not difficult to find examples of shared concerns and common imagery: Damien Hirst’s butterflies, Roxy Paine’s conjoined trees, and Philip Taaffe’s layered cosmologies are some that come to mind.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Earth ca. 1570

Tomaselli’s images inhabit a shallow space exploring the tension between real embedded objects and the illusions they project. His approach is highly detailed and encyclo pedic. But despite the visual complexity of the work for which he has become best known—composed primarily since the early 90s—his earlier pieces are quite different. For example, his work from the 1980s is visually simpler by comparison and is rooted in conceptual art and site-specific installation. In fact, some of the pieces from that period might be described as parodies of minimalism—geometric paintings executed with lines of pharmaceutical pills instead of lines of paint; three-dimensional assemblages where meaning is located in the actual objects and not with the illusion they produce. Premeditated and planned, as Tomaselli recounts, “I was executing my work vs. arriving at it.”

Over time his work has come to embrace illusion, as well as risks associated with creating paintings without a plan. This practice puts Tomaselli in the company of traditional painters, and while he still incorporates real objects into the painted surface, the pieces rely more upon emergent illusion and Mnemosyne than on the quick one-liner that can only be understood by the art insider. Tomaselli describes the path to his current work as one where he “started adding landscapes and figures and all sorts of things until, finally, it felt like I could do anything I wanted to do,” and ultimately led to “a kind of free-for-all.”

Night Music for Raptors, 2010 Photo collage, acrylic and resin on wood panel 84 X 60 inches Copyright the artist Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Two things that make Tomaselli’s work stand apart from many of his contemporaries is how it has grown broader and more inclusive over time (many artists seem to get narrower in their interests as they mature), and its accessibility to people outside the art world.

Any discussion of Tomaselli’s work has to acknowledge his interest in psychedelia and psychedelic imagery. His use of pills, pot leaves, and other psychotropic substances in his paintings was instrumental in clearly telegraphing meaning by using the object to demonstrate intent rather than illustrate or allude to it.

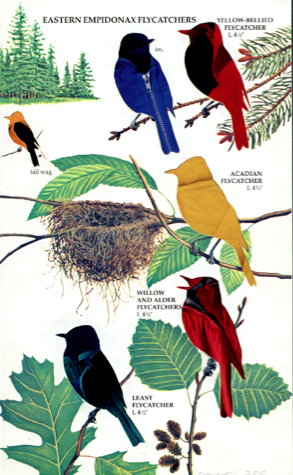

Tomaselli’s scope has expanded beyond pills and pot to embrace other vectors in the life of the mind. And as his interests have expanded, he’s broadened his vocabulary of supporting images and objects to include scientific illustration, nature guides—especially ornithology—anatomical drawing, and other illustrations based on the observation of nature. These interests are apparent in the range of his work, including pieces on display at the Brooklyn Museum. For example, The Big Eye (2009), explores spirituality as seen in meditative and devotional images. In Eastern Empidonax Flycatchers (2010), we see a documentation of natural variations. And Echo, Wow, and Flutter (2000) reveal the unexpected result of the visualization of audio phenomena.

To understand how Tomaselli has been able to take his initial interest in drug culture and stoner head tripping and enlarge it to accommodate such diverse domains of knowledge as ornithology, human anatomy, insect morphology, and the graphic representation of sound, it is useful to look beyond his use of collage and resin.

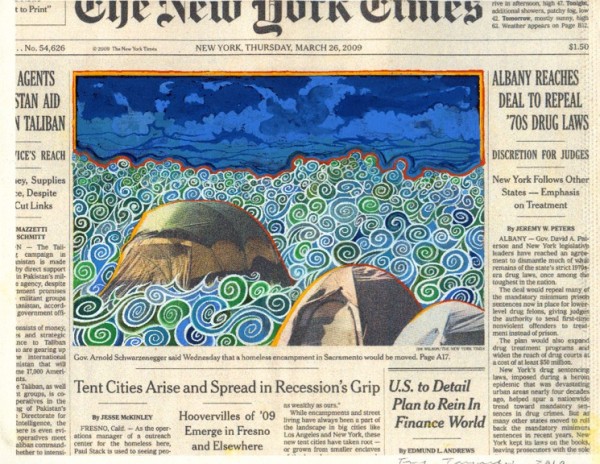

Mar. 26, 2009, 2010 Gouache on printed watercolor paper 8 1/4 X 10 1/2 inches Copyright the artist Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

In the 1960s Arthur Koestler proposed the concept of the holon to describe something that is simultaneously a whole in itself as well as a part of a larger, more complex entity. According to his theory, any subject—whether it is a specific society, an ecosystem, or natural phenome non—can be understood as a stack of ever more complex holons. Each holon is a temporary island of stasis in a transient and dynamic world. Tomaselli’s paintings would serve well as a demonstration of this theory, not only in terms of order out of complexity, but also in the range of subjects to which it can apply: a thousand butterfly wing variations assemble to form a single, giant wing; a motley collection of human parts assemble to form a single large human body.

Eastern Empidonax Flycatchers, 2010 Collage on paper 9 X 6 inches Copyright the artist Courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai

Tomaselli’s process is also intimately connected to the practice of collecting. Although typically categorized as a hobby, the first collectors were naturalists, tagging along on missions to far flung locations and drawing or preserving the natural variations found in remote, otherwise inaccessible locations. Integral to collecting are the prin ciples of organization and cataloging. Like the collector’s Cabinet of Curiousities, Tomaselli’s paintings fuse the cataloging of variations, the ordering of multiples, and the display of the results with an effect that transcends the rational ordering of knowledge.

The result makes photographic reproductions of his work deceptively inadequate. The work operates differently depending on your distance from it. This phenomenon, along with the visual effect of resin overlay, makes it essential to experience these pieces in-person. For example, what appears at a distance to be a bird might be composed of hundreds of miniscule bird wings. Besides the obvious psychedelic trope, this effect gets really interesting when the license is extended to allow both the constituents and the results to exist simultaneously, as in Organism (2005), or Blue Geode (2007). In these works, there is the tension between the view from across the room and what is seen at close inspection, resulting in an effect similar to the best stage design: a fusion of illusion and the mechanism used to support it.

Leave a Reply