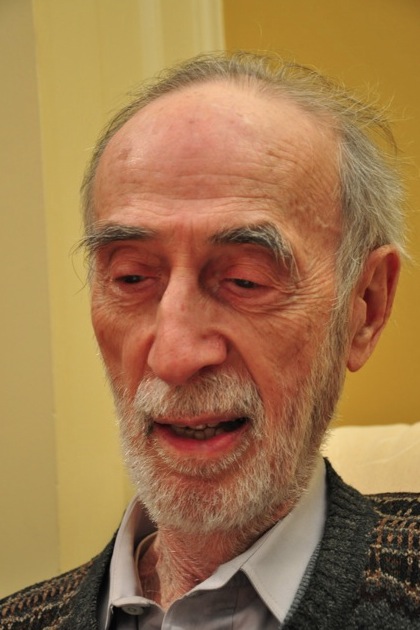

American scholar Philip Gould. Photograph by Fred Yu

I didn’t realize Professor Philip Gould was a few days away from turning 90 years old when I requested he meet me outside the Plaza Hotel. Were it me, I probably would have responded with something like “that’s quite a shlep for me, young lady.” But not Gould. He was cordial, vibrant, and more than happy to meet me on my own terms. After all, it was Gould who’d given the now infamously incarcerated Chinese artist Ai Weiwei his first-ever U.S. group show. To my reporter’s mind, interviewing him while sitting somewhere between the bronze rooster and bronze dog’s head of Ai Weiwei’s newest public sculpture seemed just the ticket.

Gould’s dossier is an impressive one: 33 years as a professor at Sarah Lawrence, along with teaching tenures at Columbia, Pratt, and Teachers College in Beijing; and a personal collection of some 6,000 objects from Africa and the East. I’d prepared some pretty generic and academic questions for him, but Gould wanted to stay on point. He was passionate about politics: the East and its love of ancestors and the West’s compulsion to topple cultural heroes as fast as we mint them. And he had more insights into Dada-ism’s reach than I’d previously imagined possible.

Well, it’s not every day you get to talk to someone who’s lived through a near-century’s worth of culture!

Can you tell us when you had your first significant encounter with the art of China? While I was at Sarah Lawrence in the 1960s, New York State developed what they called the Seed Program to introduce Chinese art to the curriculum of schools of higher learning, and so they selected 15 art history professors from around the state to join this seminar, and I was one of them. We had the best teachers, scholars, museums to orient us in this new discipline in Chinese art. It was a fabulous program, and the only condition was that you teach Chinese art to your colleges in the years after.

Sounds great. Yes, it was, and I took that commitment very seriously and have taught Chinese art ever since. The Seed Program in New York was followed up the following summer by a Fulbright summer seminar in Taipei. We had a very good leader, a curator from the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery. Besides our formal classes he would take our group of 12 or 13 people to different galleries in town. I should point out that Taiwan had been under Japanese rule for 45 years before World War II, so much of the cultural commerce was Japanese. My fellow Fulbrighters were happy to buy Japanese paintings while I preferred to wait to find Chinese works. Eventually I did when I went out on my own. I found a Chinese folding fan with a painted landscape which was later authenticated by our Freer Gallery expert as an eighteenth century work.

Is that when you started collecting? I was thrilled by my new acquisition and encouraged to forage the antique shops for more. Good paintings were hard to come by but folk pottery was plentiful, just ordinary stuff that people bought and used. When I got back to the United States I had six cases filled with the folk art. The very next year I organized an exhibition on Ming and Ch’ing Dynasty folk pottery. When my friends from Taiwan came to view the show they said, “My God, we never paid attention to this stuff.”

The bronze heads for Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads (Photograph © AW Asia) currently on view outside New York’s Plaza Hotel

It sounds like you’re good at assessing the value of things. Over the course of my time at Sarah Lawrence College I organized over 30 exhibitions drawn from my collection, or with material borrowed from museums and collectors. My main focus was on China, but the arts of other Asian cultures were included as well.

In the light of my activities at Sarah Lawrence College, I couldn’t help but pay attention to the influx of Chinese artists from mainland China. China was going through a period of detente following the end of the Red Guard movement [1967–1976], which, for artists, meant the possibility to travel abroad. Art students in China could follow two lines of study, one was traditional painting using ink, paper, and a soft brush, or a modern [Western] approach, which meant working with oil or acrylic, canvas, and a stiff brush.

Tell us more about that detente period, and how you found these artists. The artists who opted for the Western style of painting were in the forefront of those traveling to Western countries. I encountered many newly arrived Chinese artists in the streets of Manhattan. They were making portraits of people for five dollars a pop to make a living. They were without exception excellent draftsmen, knocking out terrific likenesses of New Yorkers. But I knew they had another mission, namely to live and study in the proximity of the art and artists they emulated.

Is that where you found Ai Weiwei? I recruited some of these artists to form the show “Artists from China—New Expressions” and Ai Weiwei was among them. They were very talented, and they skilled and outclassed most of the Western artists. That show was in 1987.

Tell us more about the West-East mindset of art history. First, the East. The issue for these artists was to discover the motivation of their American counterparts. Chinese artists have a long tradition of respecting their predecessors. They would often inscribe a little note in their paintings that they are working in the style of such and such an artist, who lived two or three hundred years ago. In fact, the paintings bore little resemblance to their respected antecedents, but the overture of respect was still there. The past was revered, and respect for tradition was maintained. The Chinese artists in New York discovered soon enough that a very different attitude guided American painters, who were only too glad to trash tradition as they eagerly sought to displace their predecessors. This American syndrome explains why we have so many different styles of painting, one following another in rapid succession. The drive for change and competition stands in stark opposition to the Oriental respect for tradition.

So what’s the Western psychological mindset? Diametrically opposed. The history of Western art has been one generation kicking the last generation out of place, and rejoicing!! I had American friends, artists; they took cans of paint and went to MoMA and threw it into the lobby in revolt.

Artist and political activist Ai WeiWei in meditation. Photo via aartlife.com

That’s a tall order, no? As a contemporary artist you need to win the notoriety, the publicity with the art critics, the space. It’s really a challenge to displace your antecedents and replace them.

It shouldn’t surprise you to learn that the art Ai Weiwei loved most was Dada; its artists became his model. Dada was a movement to wipe away bourgeois aesthetic values. That’s where you get the urinal. The most vulgar things were thrown in the face of the public. Well, that was bound to be trouble for him.

[PAUSE, as we look over at the Plaza, to our right. We watch what appears to be a steadily moving stream of black limos and unmarked black cars out front.]

You think this is posh? China had a very sophisticated society, certainly from the Tang Dynasty on: women enjoying a big place in court, wearing the most exquisite silk gowns and carrying themselves with such elegance and bearing, you know they played an important role in the life of the country. The point here is that China had the most advanced culture in the world in the eighth century. The Chinese wish to recapture that role … to be the top dog in the world today. China has made fantastically rapid progress in catching up with the West in industry, in manufacturing, in technology, in military prowess. Why would they not want that distinction in the arts as well?

How do you mean the “center of the world”? What does the art of the [Chinese] past do? It reflects the opulence of the court. Art today, out of China, even the contemporary art, has to represent the effort of the best again, the best of nations. It sounds very chauvinistic, I know, but countries compete. And the Chinese want to be the best.

Here is the problem. Ai Weiwei is promoting China’s standing in the arts by being exhibited and fêted around the world, but in that process he is a threat to his own country by asserting an independent voice. China has to drive a difficult course of both embracing Ai Weiwei and curbing him. Artists, in general, are a threat to the status quo because they inevitably express the sentiments that infuse society. Artists are political whether they realize it or not. The paintings by Ai Weiwei in my 1987 exhibition representing Chairman Mao were tongue in cheek representations, ironic.

Do you think that art and activism—or to put it another way, art and cultural change—go hand in hand? Yes. What artists do is concretize political sentiment. They give it a tangible form. I know that a lot of people in China right now must be desperate for greater liberalization—but they don’t openly announce it. That’s where Ai Weiwei talks for them. On the one hand his art is attractive; on the other hand it is feared. It is political [at its core] and a good artist expresses that.

Is radical change a service that “Art” provides to “Culture” in general? It’s like I just told you: art concretizes values. It gives values that are circulating in a moment of history—the ideas floating around—a form that you can see or feel or hear. You can grasp it. Of course, often artists do this unwittingly—in fact, most of the time they do. [smiles]

If you could pick a favorite work of art, from any culture or time period, what would it be?Well, I’m very partial to Chinese painting, and my favorite painting is called “Six Persimmons by Mu Chi” from around 1200. It’s small, an 8” x 10” vertical scroll. It has no chiaroscuro; it has no foreground, and no background and no light source and no color. It’s done only with brush and ink on paper—and it’s still my greatest painting.

Where do you think it’s heading—this explosion of contemporary art? That’s almost a moot question. It’s no longer what happens here or there; it’s happening everywhere. Ai Weiwei is a perfect example; he has shows everywhere. This sculpture [he points to the fountain] was planned before he got arrested. He already achieved a level of art that speaks for the rest of the world.

Do you have any advice for budding art historians or cultural pundits who might be reading this right now? I’m not worried about art historians; I’m worried about artists! Artists may be a threatened species. Look what happened to Ai Weiwei and his fellow artists. They were brutalized in prison. They have something to worry about, not historians. I’m in a safe place to speak my mind. You know, you remember, what happened in Russia! The artists there were way ahead of the West, the rest of the world. It was Russian artists who invented abstract painting, before Picasso or Braque, but they were seen as a great threat to the State. Why? Because anything that deviates from the traditional is threatening. Anything that challenges the status quo is a menace.

Other articles about Ai Weiwei early years:

“Before Fame or Jail Ai Weiwei was a Starving New York Artist”

Also, go to Artsy’s Ai Weiwei page

Leave a Reply