For those who are lost, there will always be cities that feel like home.

Places where lonely people can live in exile of their own lives—far from anything that was ever imagined for them.

Athens has long been a place where lonely people go. A city doomed to forever impersonate itself, a city wrapped by cruel bands of road, where the thunder of traffic is a sound so constant it’s like silence. Those who live within the city itself live within a cloud of smoke and dust—for like the wild dogs who riddle the back streets with hanging mouths, the fumes linger, dispersed only for a moment by a breath of wind or the aromatic burst from a pot when the lid is raised.

To stare Athens in the face is to peer into the skull of a temple. Set high above the city on a rock, tourists thread the crumbling passageways, shuffle across shrinking cakes of marble worn by centuries of curiosity.

Outside imagination, the Parthenon is nothing more than stacked rubble. And such is the secret to life in a city ravaged by the enthusiasm for its childhood. Athens lives in the shadow of what it cannot remember, of what it could never be again.

And there are people like that too. And some of them live in Athens.

You can see them on Sunday mornings with bags of fruit, walking slowly through the rising maze of concrete, adrift in private thoughts, anchored to the world by unfamiliar shadows.

Most of the apartments in Athens have balconies. On very hot days, the city closes its million eyes as awnings fall, drowning the figures below in dreams of shade.

From a distance, the white plaster and stone of the buildings glow, and those approaching from the sea on hulking boats witness only a rising plain of glistening white—details guarded by the canopy of sharp sunlight that sits over the city until evening, when the city slows—and then a quick blush that deepens into purple veils the sea and becomes night.

In this city of a thousand villages, families huddle on balconies with their bare feet on stools. Lonely men dot the cafés, hunched over backgammon, they stare at the ends of their cigarettes—lost in the glow of remembering. It is a city where people worship and despise one another in the same breath.

For the lost souls of this world, Athens is a place not to find themselves, but to find others like them.

In Athens, you will never age.

Time is viewed in terms of what has been, not what is to come.

Everything has already happened and cannot happen again, even though it does.

Modern Athens buzzes around truth that everyone believes but no one can remember. As a visitor, you must simply find your own way through the foul, dry streets, where dogs follow at a distance close enough to be menacing and walls still gape where smashed by missiles of ancient wars.

And the lingering smoke and bustle, the strange music of the laturna machine, the forever pushing of strangers.

The museums are crammed with moments that went missing from history, that are impossible to put back, that were discovered by the thump of a plough, or hoisted up from wells, or dragged in tangled fishing nets along the seabed: mossy heads, stone hands teeming with barnacles, rotten oars rowed by the current in the dream of where they were going.

The beauty of artifacts is in how they reassure us we’re not the first to die.

But those who seek only reassurance from life will never be more than tourists—seeing everything and trying to possess what can only be felt. Beauty is the shadow of imperfection.

Before Rebecca moved to Greece to develop as a painter, she flew around the world serving meals and drinks to people who found her beauty soothing.

Thousands possess the memory of her neckline, the deep blue of her uniform, the smooth edges of her navy heels, a tight bouquet of crimson hair.

She moved in straight lines, always smiling, a mechanical swan wrapped in blue cotton. In the mornings before work, she tied up her hair in a mirror. It was soft and always falling. She held bobby pins in her mouth, and then applied each one like a sentence she would never say. Her hair was dark red, as though perpetually ashamed.

It was an effort for her to talk, and so like many shy people, Rebecca found a face in the mirror and a voice that went with it. She used them like tools, to make sure it was tea that was desired and not coffee—or whether monsieur or madame might like another pillow. The real Rebecca lay beneath, smuggled onboard each flight inside her uniform, waiting for the moment to reveal herself.

But such a moment never happened, and her true self, by virtue of neglect, turned from the world and slipped away without anyone noticing.

Though her work did have its moments of salvation. She paid particular attention to children traveling alone. She often sat with them on her breaks, holding their hands, folding soft ropes of hair into braids, watching a piece of paper come alive in lines. Her dream was to become an artist—to be loved for moments beyond her own life.

She had spent her own childhood with her grandfather and twin sister, waiting for someone to come home, but who never did. And then suddenly it was too late. And the person she waited for became a stranger she would no longer recognize.

During the first seasons of Rebecca’s femininity, she sensed there was a world outside her disappointment. Her twin felt it too, and they watched each other in the bath in the dull afternoon like porcelain dolls, their lives a story within a story.

They seldom talked about their absent mother, and never ever mentioned their father—who, they were told, was killed in a car accident before they were born. When something on the television alluded to motherhood, both girls would freeze until the moment passed. For even the most subtle movement would have been read by the other as an acknowledgment of a feeling they shared in silence—a failure forced upon them.

Then came the idea of another sort of love. In bed alone, aged sixteen, Rebecca gripped the sheets and conjured the strangeness of something inside her body, something living, spiraling deeper and deeper into the swirling pool of who she was, almost reaching back into the past to look for her.

For such a quiet girl, who walked to school every day across soft fields, her red hair as wild as blowing leaves—to love without fear would be to drown in another person. A first mouthful of water; a face disappearing; the sun changing shape, a bright rim, like the edge of a bottle into which she had fallen. Then her body would fill, go limp with gentle heaviness, and drift with the current.

Her supervisor at Air France was forty-five and divorced. Her ex-husband lived in Brussels and worked for the government. Her face was very thin. She possessed an elegance that made her seem taller when she walked. She was the sort of woman Rebecca imagined her mother could have been.

When Rebecca first arrived for training, she watched videos of flight attendants at sea, paddling octagonal orange rafts as small heads (presumably passengers) peered out through clear plastic windows. She was asked if she felt capable of daring rescues.

At a six-week training camp she learned to put out fires, kick through windows, and free helpless passengers trapped upside down in their seats. And she learned to do all this in a skirt and high heels.

She was taught to disarm a terrorist with the heel of a Dior pump and disable a live grenade with a bobby pin. But if at any point she ripped her tights, a whistle would blow and she would have to start the exercise again.

The training took place in large, unmarked warehouses outside Paris. Rebecca was always reminded how lucky she was to be chosen for her profession. After a while, she just bit her lip. Most of the training, she thought, is completely useless.

The majority of airline crashes are fatal to everyone on board.

Her real job (for which she received considerably less training) was to serve food and straddle the line between authoritative and sexy. In the 1960s, mandatory retirement age for flight attendants was thirty-five, but it was expected that they use their position wisely to secure a husband before then.

She kept her small Renault Clio at a staff parking facility near Charles De Gaulle International Airport. The window washer smelled like shampoo. The seats were gray fabric.

The Muslim man who ran the garage had a small office, where he drank tea all day and fed stray cats.

• • •

After two years, she left Air France and moved home to her grandfather’s house. Many of his friends had gone to nursing homes in Paris or Tours to be closer to their children. Her sister was living in the south, close to Auch, with an older man who sometimes hit her.

Away from her twin sister for the years she spent in the air, Rebecca had become her own person. No longer one of a pair, and no longer responsible for her sister’s strange outbursts, which, growing up, had scared and repelled her.

If anyone asked whether she had siblings, honesty compelled to admit the presence of a sister. She veiled the subject by turning away. It was her life after all—and it was all she had.

Rebecca found her grandfather’s house as she had left it: the same pictures on the walls; the same things in the refrigerator; the same noises coming from the television; birds nesting in trees; the cough of a distant tractor; cool soundless nights, then morning’s cheek against the curtains; the sound of water rushing from a faucet; her grandfather whistling in the kitchen as he snipped pieces of mint leaf into a cup.

She drew either in the morning or in the late afternoon. Her grandfather watched from the kitchen window if she was in the garden. Sometimes he’d come out with coffee and a Madeleine cake. It was very quiet. Sometimes a small airplane would pass overhead. Sometimes just wind and the chatter of clothes-pegs on a swaying line. Most of Rebecca’s friends from school had moved to larger towns in search of work and adventure. Some had enrolled at universities in small cities.

Occasionally, Rebecca would venture into the dark shed at the end of the garden. Inside was a black bicycle with flat tires, oil cans, rotting window frames, cobwebs, and a tea chest of watercolor paintings, signed by Rebecca’s mother with two initials.

Her sister knew about them, but by fifteen she had shed any artistic ambition and took very little interest.

They made Rebecca feel an immediate intimacy with someone far away. They all depicted the lake that was a short walk from their cottage. In the paintings the water was calm, and in a few—two figures on a grassy bank—as though waiting for something to break the surface of the water. The sky stuffed with cloud. Tiny specks for wildflowers, and always the same two initials in the bottom right corner in red.

After a quiet year in the cottage—a year spent in the relief of not flying, of not being pretty; a year of gathering strength, painting, mustering bravery—Rebecca decided to use the last of her savings and move to Athens. She knew nobody there. She would take her sketchbooks, her oils, and a few other things from home that she thought might inspire something.

She would live in exile with her desires. She would live as she imagined them on canvas, like faint patches of starlight: hopeful, but so far away; compelling, yet dispossessed of change.

Harper Perennial, 2011, 416pp.; $14.99 (paperback).

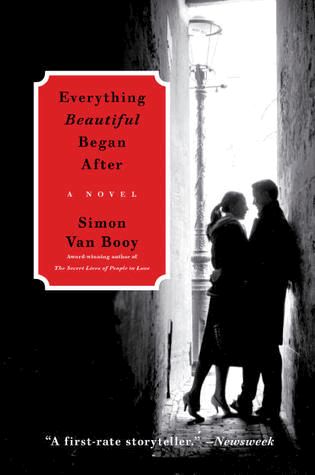

Simon Van Booy is the author of “The Secret Lives of People in Love,” and “Love Begins in Winter,” the winner of the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. Presented here is an excerpt from his debut novel “Everything Beautiful Began After,” published this month by Harper Perennial. The novel is about “…longing and discovery amidst the ruins of Athens.”

Van Booy is originally from rural Wales, and currently lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and teaches at the School of Visual Arts.

Leave a Reply