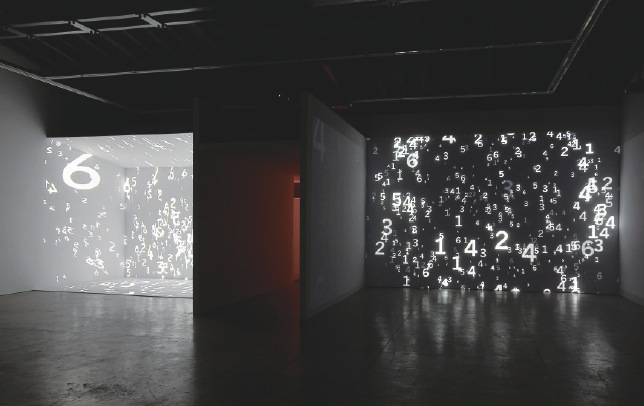

Installation view of Charles Atlas’s video projections “Plato’s Alley,” 2008 (left), and “Painting by Numbers,” 2011. Photo courtesy Luhring Augustine Bushwick

CHARLES ATLAS, “THE ILLUSION OF DEMOCRACY”

Luhring Augustine Bushwick, 25 Knickerbocker Ave., through 5/20

After more than a year of renovations, bluechip gallery Luhring Augustine has finally opened its Bushwick outpost, in a nondescript gray warehouse building with a polished exhibition area. To consecrate the space, Luhring presented a magnificent show of video works by Charles Atlas.

Called “The Illusion of Democracy,” Atlas’s three large projections are brilliantly understated, taking as their subject six simple numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. In “Painting by Number” (2011), the digits (hundreds of them) float by as if part of a cosmic ticker tape. They weightlessly snake along three walls, explode from the center like a supernova, suck back into the middle like a black hole, or spin like a celestial pinwheel. These swift changes in direction are powerful enough to elicit bodily reactions; viewers instinctively lean forward when the numbers pull inward or move back as they burst outward

If that piece feels corporeal, the other two videos play with the mind. “Plato’s Alley” (2008) has twitchy bars and grids that slowly build up through computerized mitosis to fill the white cube it’s projected upon. Numbers suddenly occupy each box within the grid like a giant Keno board, before coming down in a flurry. The biggest projection, called “143652” (2012), has bright colorful bars that slowly sweep across six giant digits, transposing their placement and changing the tone of the background. This pattern ends when the numbers become a glorious expanse of twinkling stars.

What makes these works most magical is Altas’s power to turn six boring numerals into things of grace and near limitless capacity. If Luhring Augustine keeps mounting exhibitions as good as this one, we should hope they stick around Bushwick for a long time.

MAIDER LÓPEZ, “POLDER CUP”

International Studio & Curatorial Program, 1040 Metropolitan Ave., through 3/10

Maider López’ “Polder Cup,” 2011. Photo by Maider López/SKOR/Witte de With/ISCP

Last year, Basque artist Maider Lopez set up four soccer fields near Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, for a day-long tournament. Far from regulation, these homespun pitches, in various sizes, were arranged on a lowland cow pasture, with murky irrigation canals cutting through them. The exhibition at ISCP included group portraits of the teams, an aerial shot of the fields blown up to mural size, walls painted grassy green with white lines, and two videos of all the action. But the tournament itself, called the “Polder Cup,” was the real star of the show.

In the videos, we see how the contenders had to rethink the game, given the strange terrain. Teams position themselves on both sides of a canal as a general strategy, kicking the soccer ball over the water. (Though officials occasionally have to scoop out soggy balls with nets.) Players fall into the channels more than once, and one guy looses a shoe in the muddy depths. That’s not to say these amateur competitors don’t enjoy themselves—everyone seems to have a jolly time, with smiles and laughs and backslaps exchanged throughout the championship. Outside the actual competition, spectators float across the fields in canoes, and a marching band plays spirited tunes as dairy cows munch on grass in the distance. These games are nice to watch in the gallery, but, man, they would be so much more fun to play.

ENRICO MIGUEL THOMAS, “NEW YORK CITY ABOVE AND BELOW”

City Reliquary, 370 Metropolitan Ave., through 4/29

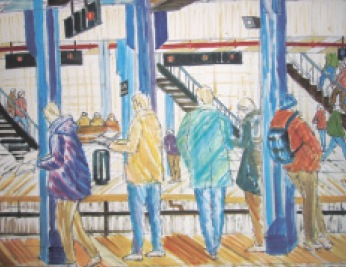

Enrico Miguel Thomas’s “59th Street.” Photo courtesy of the artist / City Reliquary

Enrico Miguel Thomas has been dubbed “The Subway Artist of New York.” (The tagline even appears at the bottom of his e-mails.) That’s because he can often be found making drawings of subway stations throughout the city—and he has created hundreds of them in the past few years.

In his practice and his style, Thomas is a kind of post-post-Impressionist. He works quickly, propping his easel on sidewalks and inside the transit system (72nd Street, Union Square, and 34th Street-Herald Square are favorite depots) to compose lively pictures in colored marker, sometimes on white paper and sometimes on free subway maps provided by Metropolitan Transit Authority attendants. These humble materials are meant to demonstrate that you don’t need money to make art.

Stripes and slashes imply the hurried movement of commuters darting up and down stairs and trains swooshing in and out of stations. Stillness in these pieces often comes in the form of token booths or hot-dog carts—their boxy structures offering a sense of stability. Other times, passengers themselves are static, as in an illustration of two homeless men in puffy coats snoozing upright on a bench on the Union Square platform. Whether hidden or loosely sketched, faces never have much detail in Thomas’s art, as he concerns himself with entire spaces rather than individual personalities. These works fit in perfectly at the City Reliquary, a place as devoted to preserving and displaying New York’s oddities as Thomas is to recording the vivacity of the subway ecosystem.

Leave a Reply