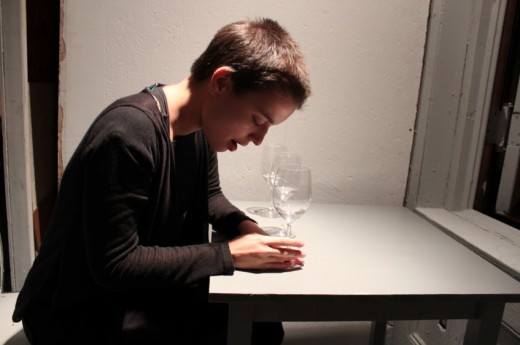

Performance artist Jessica Hirst from Spain at Grace Exhibition in April.

A giant poster of a brain tells you you’re at the right apartment. Under the screaming wheels of the elevated J train, and up the flight of stairs, is a sizable loft painted in gray.

Grace Exhibition Space, a converted loft at 840 Broadway, is one of the few performance art galleries in New York City, ridding itself of a stage and focusing on the immersion of artist and audience. With a suggested $10 donation at the door, the gallery hosts artist talks and art events every other Thursday and Friday, providing several hours of performance by both local and international artists.

Filled with professors, students, the young, the old, the curious, and the frightened, Grace Space is the kind of Friday-night hangout where you’ll drag a friend or date by the arm to come and see something they have never seen, and will never see again. Where, in a single performance, an artist can tax your imagination and push your comfort level to unexplored or previously ignored moral perspectives while you’re sitting idly on a bench with a drink between your legs. Here the barrier between audience and performer dissolves, and you’re encouraged to take action, to participate in the full spectrum of human experience in all its beautiful, humorous, bold, and nightmarish qualities—all created by the shared dream of a mass of people. On each night, and in each performance, the human body is redeemed from the mundane and made anew.

Brazilian performer Luisa Nobrega attempts to break wine glasses while screaming for three hours.

Performance pieces at Grace Space can run from five to 20 minutes, to several hours, the time being dependent on the willingness and resolution of the artist. Each inch of humanity is explored, from the simple act of transferring water with a spoon to a partner’s bowl, to the complete surreality of eating a bowl of Life cereal naked while waiting for a metal pot containing water and Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time to boil on a plug-in hotplate.

“We like to say, what God took seven days to do, we do in ten minutes,” said Erik “Hoke” Hokanson, a performance artist and director at Grace Space.

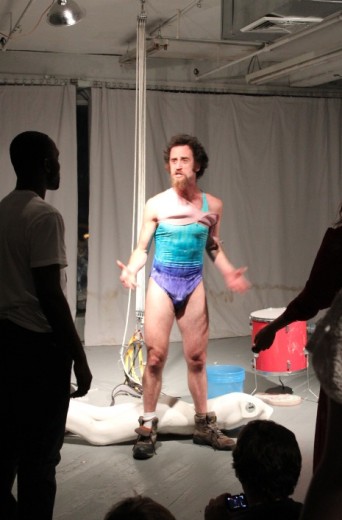

New York City artist, Mathew Silver presented a self-help course to awaken the inner child. Photos courtesy of Grace Exhibition Space

“It took me years to learn this art form,” said Jill McDermind-Hokanson, founder and director at Grace Exhibition Space. She’s the reticent one of the couple, but is the spark behind the busy gallery. “Performance art comes from fine art, like painting and sculpture. I just keep getting fascinated by it.”

After coming to New York City, and seeing a need for a venue for the art form, Jill started Grace Space in 2006 with her friend, Melissa Lockwood, whom she met at the University of Iowa. Jill graduated with a master of fine arts and a master of art in intermedia and video and studied under Hans Breder. She became interested in performance art through filmmaking because, she said, she found herself “projecting.” She’s been practicing performance art since 2000.

Jill was introduced to Hoke after meeting him four years ago at the Fountain Art Fair in Miami, where he was one of the organizers. Hoke, who has a hobby building working guitars (with 75 or so in a storage locker somewhere), described himself as “primarily an object maker,” and was new to performance art until he met Jill. It was only after her encouragement that he became interested and started performing his own pieces.

“[Performance art] is far less encumbered with rules, and it was liberating,” he said. “Unlike other art forms, it’s not confined to materials and technique, concepts and personality. Discovering performance was eye opening to me. I was always afraid I would screw it up, but you learn you don’t have to screw it up, just do.”

Since then, the Space has been curated by the recently married couple, and has hosted over 600 original performances, giving local artists such as Mathew Silver (from the New York subway stations) to foreign artists like Jessica Hirst (from Barcelona) an intimate venue to show off their craft. Both the professional artist and learning graduate student are welcome, with only one stipulation: their work has to be genuine.

“We’re like a community,” said Jill.

“The curating at Grace Space is really important. We get people who appeal to us. We go to these festivals and see what we think is really strong and we send them an email.”

Colombian artist, Carlos Monroy dancing samba for the speed dater Mona Kamal. The card chosen by Mona was: Hi, my name is Andrea Fraser. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“We make a big point of meeting all the artists,” said Hoke. “[We] have them come in and let them get a feel for the place.”

“Sometimes I let the artists go in the order they want,” but he admitted that they usually want to “finish off with a big wild mess of a performance.”

Jill and Hoke usually schedule each artist six months in advance. After they send a friendly email to the artist, they follow up with a formal letter so an artist can use it to get funding. Since their gallery is not yet a non-profit, each artist has to pay their own way to New York, either through a grant, sponsorship, or from their own pocket.

Seeing a need and having a desire to cultivate performance art talent, Jill and Hoke often go out of their way to be as accommodating to visiting artists as they can, buying them meals and allowing them to stay at their three-bedroom Bedford Avenue apartment for free, even if they’re meeting for the first time.

“There’s a day or two of feeling each other out,” said Jill about having traveling artists stay at their apartment.

After a workshop at the exhibition space, they took Finnish artists Päivi Manunu and Ilari Kahonen, as well as Art Institute of Chicago graduate students Sabri Reed and Autumn Hays, her boyfriend Brad, and their intern Ryan Hawk on a night of wining and dining in the private room of the Japanese restaurant “Qoo” Robata Bar, on Metropolitan Avenue.

Monroy trimming a shape of a hearth on his hair for one of his speed daters. The card chosen by the dater was: Hi, my name is Marcel Duchamp.

With a round of saké and a few plates of tempura vegetables to start the night, the conversation shifted from politics to movies to books to performance art, with no word on what would happen the next night. There’s anticipation for each piece, with no want and no hurry to spoil it.

Ilari, who has been involved in performance art for four and a half years, was celebrating his 50th birthday. Sabri sat in repose. Asked what was the matter, she said she was just “taking it all in.” She flew into New York from Chicago the night before (Wednesday), performed Friday night, and flew back Sunday.

After another round of saké, with “cheers” and “saluts” heard from end to end, three platters were set out with rolls of eel, tuna, and salmon, and with clusters of orange salmon roe, shrimp tails, and swordfish—each an aquarium on a platter, in shades of pink sashimi. When the night was finished, Jill and Hoke paid the bill before anyone noticed.

“You see some really, really respected people from their countries,” said Henry G. Sanchez, a faculty member and teacher of digital media for the School of Visual Design, who frequents the gallery often.

Carlos Monroy, who traveled from Colombia, is such an artist. He’s involved in a long-term workshop and internship at the Hemispheric Institute for Performance and Politics at NYU. On May 18th he performed a piece at Grace Space titled “Art of Speed Dating,” where he played the role of a speed dater, asking curious viewers to “date” him by sitting down with him at a table lined with rows of nametags with descriptions of specific actions. Viewers were then asked to choose a nametag to put on Carlos, which he then had to act out. This forced him to have a simple conversation, to put on high heels and a skinny dress and perform a salsa dance, to strip, or to go on all fours with a collar around his neck and act like a dog. Carlos’s next performance will be at La MaMa experimental theater club in Manhattan.

“There are so many actions that happen in a performance, but the more I do, it kind of gets more to the point, that it’s not about the action,” said Carlos. “It’s about being there experiencing that and kind of being somehow willing to live that thing, experimenting it. Even if you’re not a performer and just being there.”

“That was a very smart piece, not only fun and interesting, but calling from an art historical perspective,” said Henry. “Carlos really stood out. That’s the best one he’s done so far.”

A newcomer may see performance art as bizarre or random, and indeed it requires the spontaneity of live performance, but often there’s a careful process of thinking out a piece, making sure every gesture or object is not mistaken for symbolism, for unintended or ambiguous meaning. If questioned about the intention of a piece, a performer will often talk about an entire philosophy of what, why, and how, although exact meaning is sometimes hard to pinpoint, with the listener playing the role of a frustrated lepidopterist failing to pin down an elusive butterfly.

“Art is about communicating, not about keeping secrets,” mentioned Hillary Sand, a performance artist and also volunteer at Grace Exhibition Space.

This communication starts with the artist’s body through what is called action. Marilyn Arsem, a performer and teacher of performance art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, wrote in a 2011 essay detailing what she believes performance art is: “The artist uses real materials and real actions,” she said.

In line Ms. Arsem’s definition, I believe a performance artist’s prime material is their body, using it to interact with both the space they perform in and the audience that surrounds them. Their imagination for a performance is bound by the limits of their body. This means a piece may also include male or female nudity, and it may be explicit and challenge the edges of decency and morals of the viewer, but like any common object, a lamp, a bowl, a rocking horse, a screaming voice, an exposed penis or a pair of bare breasts, the artist will use the body as an art object, creating action to transcend something material into an idea. This idea is then left for the viewers to discern for themselves, with no single answer being right or wrong.

The artist Carlos adds, “People get shocked and people feel they need to understand, and because of that people run away from performance art instead of going closer. I’m trying to get people closer [to performance art], not just in an appealing way, so at least when you go home you can at least talk to yourself—I had fun today. If after you have fun—you’re able to think of other stuff, I will say, ok, my work was really well done… My point my idea is—after you have the fun, somehow a door opens and you think of other things.”

“I think good performance art results in more unanswered questions than answered questions,” said Hoke. “It’s not about acting, it’s about action. Action belongs in performance art. The work that we show is art through action—conveying the immaculate through the idea of movement!”

“You can have this very simple act,” said Jill, “and it has this intensity of purpose.”

An intensity of purpose they said is found in the gray space of a performance, when the primal gray matter of the brain reacts to the spontaneity and inventiveness of a performance.

“You’re absolutely riveted because this artist can keep your attention,” said Hoke. “A lot of these performers are revealing, and the audience can get a sense of who the artist is.”

A typical Friday for the two has them running and working through the night. During an event, Jill and Hoke meet old friends and greet and introduce new acquaintances; they fix lighting, and help set-up each performance; they announce each artist by using a bullhorn to grab the audience’s attention, making sure everyone is quite and gathers around the next piece. By the end of the night, they’re exhausted with several weeks worth of work finally done. They film each performance for an archive, which they make available by appointment during the week.

With the end of each performance, and after the audience has cleared, comes a sober concern from each performer of what others thought of their piece. A vulnerability and shyness that somehow was masked returns and is exposed through conversation lasting until the early morning. Jill and Hoke give their advice and their thoughts with each artist listening with careful attention. The artists were asked to keep their spaces messy throughout the night, because they’re told it’s part of the performance and theme of the night. But now it’s 12 a.m. it’s time to close; the artists are then asked to clean up their spaces before they leave, with everyone remaining helping with mops and brooms, careful to leave remnants of their mess, a scrawled wall, feathers from shredded pillows, a piece of rope, mementos of the artist and the night.

Leave a Reply