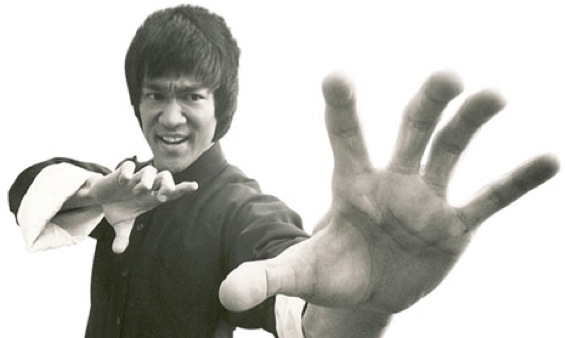

Bruce Lee stands in the ready position inside the entrance to the New York Martial Arts Academy, in Williamsburg. He is shirtless, bending at the knee, twisting slightly to his right, every muscle on his rippling torso obedient to his will.

Bruce Lee stands in the ready position inside the entrance to the New York Martial Arts Academy, in Williamsburg. He is shirtless, bending at the knee, twisting slightly to his right, every muscle on his rippling torso obedient to his will.

It’s a movie cut-out of Bruce, mind you, a still photograph taken from a fight scene in Enter the Dragon. But this image has been enlarged to life size, and is lifelike enough for me to approach with reverent caution.

This is the enduring, iconic image of Bruce Lee, in a fight to the death, as it should be. His face and chest are slashed and bleeding, but his wounds are only skin deep. Blood streaks like war paint down his glistening body. His hands are up, his eyes are ablaze.

Andy Warhol, eat your heart out

Now, somewhere in my memory, I knew Bruce Lee was short. But gradually, as I step close enough, I see he’s not only short but slender, too. I’m standing over him, looking down on him, a little surprised at how much narrower his shoulders are than mine.

Dino Orfanos, the academy’s lead instructor, is watching the whole scene from behind me.

“Five-feet seven, a hundred thirty-five pounds,” he says.

Orfanos steps forward. To my relief, he’s not an alpha-male vegetarian, pruning his words like the leaves on a bonsai. He’s a 51-year-old Greek with an Astoria accent. Curly white hair with a mustache, heavy-set, a silver chain around his neck. He could be the guy on the stool beside you when the Jets game’s on.

Yet Orfanos was trained by two of Bruce Lee’s most decorated students in Jeet Kune Do, the martial art that Bruce devised in the 1970s. To break the ice, I tell him that my favorite Bruce Lee fight-scene of all time is in the martial arts tournament from Enter the Dragon. It’s when Bruce matches up against O’Hara, a big white ogre of a bad guy with a knife scar down his face, played by heavyweight world-kickboxing champ Bob Wall.

The best fights to me were always the ones when the fists of fury pulverized some rock-jaw of a Green Beret-gone Blackwater.

O’Hara more than fits the bill. He meets Bruce in combat on the island fortress of Han, a renegade Shaolin monk who broke the warrior’s code by trading in his oath for a lucrative life of crime in the Hong Kong underworld. Bruce is there in deep cover, a promising young Shaolin monk on a secret mission to break up Han’s criminal empire and avenge the grave dishonor brought upon the order. He is under the guise of a contestant in the martial arts tournament.

Say what you will about kung fu movies, they don’t split hairs over good and evil.

At tournament time, Han sits on a throne of gilded wood and arranges the fights. It is he who picks Bruce to fight O’Hara, delighting in the prospect of the big man making mincemeat of the stranger. Until the very last moment, however, Bruce isn’t told whom he will fight.

“Mister Lee, are you ready?” the referee asks. Bruce nods and watches with interest as the referee moves through the crowd in search of his opponent.

When O’Hara stands up he’s like a grizzly on his hind legs, two heads taller than any man around him in a karate uniform, a malevolent glare on his face.

Bruce lets his eyes widen a touch in response, as though he is slightly amused at his own disbelief.

The crowd clears a path for O’Hara, whose bearded jaw is clenched so tightly it’s like he can barely restrain his urge to kill for the few seconds it takes him to reach Bruce. When he does reach the fighting area, in lieu of bowing, he holds a board right in front of Bruce’s face and breaks it in half with his fist. Does Bruce flinch? Nah. “Boards don’t hit back” is all he says.

The two men square off at arm’s length, hand across hand, close enough to look each other in the eye. O’Hara regards Bruce’s poise with apprehension; Bruce stares back with the fleeting calm to be found at the center of a hurricane. The outcome is determined right then. O’Hara gets hit and dropped with one punch. The crowd applauds politely. He gets up rubbing his jaw, lines up again, a bit hurriedly this time, and gets dropped again, just as quickly. The polite applause resumes. Bruce’s hands are just way too fast for O’Hara, who flies off in a rage. And man, Bruce punches hard!

Orfanos stops me before I go any further. My recollection of the fight scene has evidently hit a nerve with him. He pulls me by the elbow over toward him, so that we’re facing each other.

“What Bruce is doing there is what we call the straight lead,” Orfanos says. “We teach to lead punch with your strong arm.” To demonstrate, he throws a flurry of straight right leads at my face from different angles, his softball-sized fist halting each time near the tip of my nose. “Like a boxer fighting Southpaw, see? Only these aren’t jabs we’re throwing.”

Indeed, the straight lead that Orfanos demonstrates is more of a thrust than a jab; his whole body lunges forward behind his fist. It’s a high-percentage punch, thrown with power, and since it doesn’t require the striker to over-commit his body, he stays relatively far away and protected. The technique, I later learn, was one that Bruce Lee appropriated from fencing.

“We also teach crosses and hooks with the back hand,” he said. “It leads to combinations that a lot of people aren’t used to.”

Orfanos opened his first Jeet Kune Do academy in Long Neck in 1985. The Williamsburg location, his second, opened in May. He and his partner, Peter Papamichael, believe it to be the only academy of its kind on the East Coast.

Papamichael was a teenage martial-arts student in Little Neck when he met Orfanos. The two-story building on North 8th that’s home to the new academy is his. “I could’ve turned this place into condos,” he told me, “or I could have turned it into this.”

The place is an old factory with two spacious floors. It’s fully equipped. A practice room on each floor. A sparring cage upstairs. A lounge area. On the day I was there they were putting in a gift shop.

While Orfanos and I talk, a martial-arts fitness lesson for five-year-olds begins in the other room. It’s not scary at all, just three little kids doing kung-fu aerobics. Adult classes are the main focus of the academy.

“I love it here, this is a wild neighborhood,” Orfanos said of his block near Bedford Avenue.

Orfanos says the actual number of students enrolled is double what they projected. He says he is optimistic that Bruce Lee’s martial art will find a home in Williamsburg. “A lot of people don’t realize it, but Bruce was very anti-establishment. He stood up against 300 years of obsolete tradition.” I ask Orfanos to elaborate.

Every ancient fighting style, he says, favors a certain form of combat, be it striking, grappling, trap locks, or weapons. Each of the respective founders devised a system of rules and classical forms to favor his own strengths. Once the style was set, students learned it by repeating the same movements again and again, a process that Bruce Lee said teaches them to imitate, not to fight.

“If you follow the classical pattern,” Bruce wrote, “you’re understanding the routine, the tradition, the shadow — you are not understanding yourself.”

“We don’t teach a style,” Orfanos says. “We teach the kinetics and the physics of fighting.“

The word master isn’t used by students to refer to their instructors at the NY Martial Arts Academy. “Who’s the master?” Orfanos asks. “No one is. We’re not even masters of our own destiny.” Instead, the instructors are called sifu, which means teacher. Black workout pants and black t-shirts is the standard training outfit. No one wears a karate gi, for the simple reason that no one wears one in a street fight.

“We’re trying to minimize as much as possible the differences between in here, and out there,” he says, gesturing toward the door.

Orfanos doesn’t believe in belts, either. He says they encourage complacency. So then, how does he determine competence? “By skill,” he deadpans.

Orfanos arrived at Jeet Kune Do after 15 years of traditional martial arts training in Kung Fu and Brazilian jiu-jitsu. He tells a story from his days early of training under the renowned grandmaster of Brazilian jiu-jitsu Reylson Gracie. During one sparring match, Orfanos picked his opponent up off the ground and body-slammed him onto the mat. The class went silent, and the instructor reprimanded Orfanos on the spot.

James Orfanos has clearly read the same Bruce Lee book that I have. James is Dino’s son and a young instructor in his own right at the NYMAA in Williamsburg. In a promotional video on the academy’s web site, he repeats the same important distinction between a fight and a sport.

“There’s a lot of arts that deal with — like take a ring sport, like Thai boxing. You put two guys that are on the same weight class, same skill level, and they fight within rules. But when you take out those rules, a lot of things change. There’s a lot of things we teach here that might be considered ‘dirty’ fighting. But it’s what’s going to get you home safe at night, and that’s really what I want to teach my students, because they’re good people.”

All this talk of kicks, knees and elbows reminds me of Mixed Martial Arts — the cage-fights of strikers versus grapplers. And not just because the Williamsburg academy holds its sparring sessions on a spring-loaded mat in a caged octagon upstairs.

Like Bruce advised back in the early 1970s, MMA fighters borrow techniques from a variety of fighting styles, without pledging allegiance to any of them.

MMA owes an obvious debt to Bruce Lee, with some of its leading practitioners even crediting him as the original cage-fighter. Eddie Bravo, for one, an MMA fighter and jiu-jitsu world champion, spoke to Bruce’s influence in a mini-documentary on Youtube.

“Everything he said was always about don’t get locked into a style,” Bravo said. “Don’t be a slave to a style. Dissect it, look into every style. And taking what’s good and adding it to your game. To have no style is a style.”

Now that Bruce Lee’s fighting prowess is beyond dispute, isn’t the philosophy stuff really a bit much? The academy in Williamsburg teaches a one-hour philosophy class every Saturday morning. Orfanos says that it’s a complementary part of the training, though not required.

Aren’t the non-cage-fighters among us entitled to at least raise an eyebrow to this? Isn’t being disabled and taken down by a perfect arm-bar technique enough? Must we also be made to suffer our tormentor’s disquisition on Yin and Yang?

Jeet Kune Do, like cognitive-behavioral therapy and a raft of self-help books, emphasizes that how we think about something will ultimately decide what that something is. “What you are is because of your habits of thought,” Bruce Lee writes. And habits of thought, he reminds us, are subject to control.

Predictably, combat is the master metaphor for an individual’s conduct in the face of adversity. Really, is there a better one? Combat as a reminder to remain humble and persevere in the face of doubt. Combat as a reminder to trust what you see and act on what you want. And so on.

It is a philosophy with something to say about remaining present in the world.

Typical of warrior philosophy, Jeet Kune Do concerns itself with truth as an outcome of events, rather than as an absolute The idea is to prepare to be your best at the appointed time.

Martial arts, like any strenuous exercise, soothes the estrangement between body and mind.

The physical exertion of training heightens the martial artist’s perception of movement, distance, timing, rhythm.

The leap from there to a philosophy of life is surprisingly short. Perception, not knowledge, is what determines truth in Jeet Kune Do. Truth is fleeting, and only barely visible. “Don’t think,” Bruce scolds a young pupil of his in Enter the Dragon, “feel.”

Orfanos and I are sitting in his office. He has been holding forth for quite some time about philosophy and martial arts, imparting combat tips along the way. I learn a lot in a short amount of time.

At some point, however, he notices that I’ve stopped listening. We’re sitting across his desk from one another. He leans back in his chair for a thoughtful moment, and then leans forward.

“Lift your arm so it covers your ear like this,” he says, pointing his elbow straight ahead. I do as I’m told. He reaches back and, placing his wrist on the desktop for balance, cuffs me with a roundhouse that lands squarely on my raised arm. The impact causes my forearm to bounce off the side of my head.

“Not much of a block, is it?” he asks. “So why are women much smaller than you being taught to block punches with her arm up like that? Does that seem like self-defense to you? A martial artist is trained to hit and avoid being hit.”

His point, as I straighten the hair on my ruffled temple, that a martial art is a true form of art. And that the true martial artist is one who aspires to the freest form of self-expression.

To learn more about NY Martial Arts Academy and how to enroll for classes, click here.

Leave a Reply