Myk Henry, an Irishman from Dublin, had just come back to Brooklyn from an arts festival in South Korea. He walked around his apartment and into his kitchen making coffee, and placed the mugs on the dining room table. One month had passed since we had last spoken. Before his trip to Korea he said that he had been getting burned out on performance art. Although now, he felt reinvigorated. “You look down a side street and you see the neon signs blinking and the people rushing by and it’s like, woosh!” he said. And he is amazed at his own prolificacy. Realizing he’s participated in eleven performances in 2012 alone, it doesn’t seem like Myk Henry is slowing down.

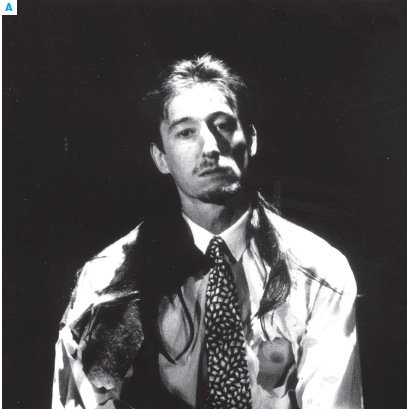

An artist who works with video, installation, and performance art, Henry is tall, broad shouldered, and speaks in a colorful, descriptive way that brings up images of the many specific and odd experiences he’s lived through. He gives the impression that life could be, or is, at least for him, an art form. (He also shares an uncanny resemblance to actor Adrien Brody.) He works as an interior renovator by trade and lives as an established artist by discipline.

Henry lived through Williamsburg’s early “Warehouse” scene in the late 80s and early 90s, helping create art exhibitions in burned-out factories. Those events attracted creative minds who wanted to keep the bright lights shining at night, and police and fire marshals who wanted to shut the bright lights off before the events had even begun. He’s traveled throughout Europe, working with many art organizations and collectives, and has recently returned from several performance art festivals in South Korea.

Henry lives off the Nassau G train stop, where Greenpoint meets McCarren Park, acting as a buffer between the traditional Polish neighborhood and a now-upscale Bedford Avenue, which has changed dramatically since he moved there in 1986. Those were times when, by night, one could see the Manhattan skyscrapers above the old warehouses. McCarren Park would be empty, except for a few muggers, bums, and people in their mid-twenties to early thirties holding each other up by the shoulder, stepping out of bars with legs crossing each other, slumping in a tangle to the park benches by the baseball fields lit-up by the tall floodlights.

In the late 80s and the early 90s Williamsburg had two bars at opposite ends of the neighborhood: one in the north and the other in the south—the Right Bank, on Kent Avenue and Broadway and the Ship’s Mast on Berry between North 4th and North 5th streets; the first café was the L Café on North 7th and Bedford which opened in 1992. Williamsburg at this time was a neighborhood of abandoned factories, thieves, garbage, and drugs, where needles and crack vials could be found strewn down Kent Avenue, and industrial spaces, like the Old Mustard factory, were taken over by bohemian artists who promoted raucous art events by what is now called the “East River State Park.” Those warehouses have been torn down, but a few concrete slabs remain.

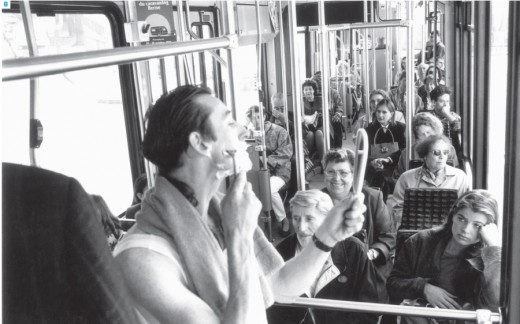

Tram happenings: Geneva, October 1996. Shaving performance (Monday morning). Boarded the tram 12 at Carouge 11.00hr in the direction of Moinsullaz. Well dressed wearing a suit and tie, I carried with me a fold out stool, a metal basin, and a briefcase. The briefcase contained a thermos flask full of hot water, a mirror, a scissors, shaving foam, a coat hanger and a towel. I clipped off my beard shaved and left the tram ten minutes later. Public reaction: One woman immediately changes her seat when she sees me taking my tie off. Old man: “I hope you’re well shaved. I think you missed a spot” Whilst pouring the soapy water out the door and onto the street one woman obviously offended and in a hurry to get off the tram says: “I can’t believe it. First he shaves and now he’s blocking the doorway of the tram. Public transport worker comments aggressively: “Next they will be installing toilets on the tram.” Photo by Didier Beguelin (Geneva)

Henry moved to New York from Dublin, Ireland, after his father, a department store owner, refused to consider handing the family business over to him, saying: “Go to university young man and get a degree in business and we can revisit this subject when you have achieved that goal.” Wanting to travel to the States with a childhood friend, the plan was to go to California, after first stopping in New York. “Originally I was preparing to come over with my best friend. As teenagers we spent every day together, but he let me down at the last minute. I ended up posting a notice on the YMCA bulletin board in Dublin, and some guy responded. We traveled together to New York and were picked up at JFK by some friend of his who took us to his house in Morristown, New Jersey. He threw both of us out after 10 days, and I only had $1,000 on me. Within two weeks I was down to $500. I was really in a tight spot.”

Needing a job and a place to stay, he went to the 42nd street YMCA in New York City, and was told to try to contact Father Pat Moloney at the Community Center on the Lower East Side on East 9th Street. As recently as April 13, 2012, the New York Times ran a character study on Father Pat, mentioning a British intelligence officer who called him the “underground general,” of the Irish Republican Army. Hearing Henry’s story, Father Pat took him in and let him stay in the apartment of his brother John, who was being held on gun running charges in Long Kesh prison in Northern Ireland. Long Kesh housed paramilitary prisoners during the Troubles from mid-1971 to the mid-2000s.

Looking for a job, Henry used a contact that his neighbor in Dublin had given him. A building contractor named Kieran McGrath, who was originally from Tyrone, told Henry that if he was ever in need, he should talk to his brother Tom. Finding Tom, he approached him, mentioning the brother’s name.

“Tom, I am your brother Kieran’s neighbor from Ireland. Do you have a job? And he said, ‘Yeah, I manage this underground casino, would you be interested in dealing cards? If you want to learn how to deal blackjack, Vinny our teacher will show you how.’ These clubs were run by the Irish Mafia, The Westies. I was in with The Westies at 19 years of age. My code name was Blaze, and they’d say ‘Yo Blaze go to 64th street.’ It was a lot of fun. They gave me a shift at the big club on 18th Street and 1st Avenue. On a busy night there would be like three hundred people in the club. At 8:30 a.m. there would be a queue outside the bathroom and inside you would see people shaving and putting on ties getting ready for work. We had this giant bouncer named Tiny. When he walked passed you, the floorboards would kind of sink. He had a frontal lobotomy and a metal plate in his forehead so he was kind of slow. Overall, I had no idea who I was rubbing shoulders with. When the cops busted the club it would usually be on a Thursday evening from 8 to 9. As soon as the cops would clear off a van would be waiting outside with tables and chips to replace those the police had just confiscated. You’re back up and running again pronto. If the owner Johnnie Mac was arrested we knew that he would be released quickly, since he knew the local precinct sergeant. And there were a lot of Irish cops on the force back then. But then they changed the busting laws, so I wanted to get out because I was afraid of being deported. It was like something out of the movies and I was the bad guy! That was my first job. It’s a social thing to deal cards, and to deal cards under those circumstances was like you were brewin’ in the prohibition days.”

Cut off my clothes and hair. Galapagos Art Space, Brooklyn, New York. October 1996

Moving to Williamsburg in 1987, Henry became part of the bohemian art scene in Brooklyn that was being decimated by the AIDS epidemic, and at the same time growing with an influx of like-minded artists who were part of a scene that would come to be known as Immersionism. Living in an apartment at Havemeyer and Roebling streets with his then girlfriend Anna Hurwitz, it was she who first got Henry interested in art. “Anna introduced me to culture. It had a nice feel about it; it felt like we were renegades, pioneers. There was lots of empty space. My roommate Martin Eastwood, who was from Northern Ireland, told me about the Lizards Tail. We used to work together as dealers in the club, and he was interested in music. When I went there for the first time I really loved the cozy, underground vibe and decided not to tell my girlfriend about it for a few months. I wanted to keep it as my own little hang out. Eventually, I told her and she also became friends with everybody and an integral part of the warehouse core group.”

The Lizard’s Tail was a cabaret on South 6th Street under the Williamsburg Bridge started by Terry Dineen and the late Jean-Francois Pottiez, and was part immersionist culture, or what Suzan Wines in Domus Magazine called “immersive culture.” “It [immersionism] blew out of a collective desire to work in a warehouse, to find a place in Williamsburg so we could showcase a lot of the performance and arts, to make it a sort of living experience, so we knew we wanted to make something community-based,” said Terry Dineen. “There are no words, it was the Cat’s Head—that was the spirit—an incredible spirit—a very international spirit. Korean Jean-Francois really spearheaded that. There was no question if it wasn’t going to be done; there was a driving force in our belief in each other and what we were doing. We were pioneers of the area—pioneers of the warehouse scene. People were coming across the east river from Manhattan in canoes.”

“Immersionism” was the art scene that took place in Williamsburg during the late 80’s and early 90’s, showing performances and multi-media works in abandoned warehouses and factories, including two that were called the Cat’s Head and the Flytrap, both of which stood on what is now the East River State Park.

Henry took out several old photos and placed them on the table, wiping them off, making sure there weren’t any coffee rings on the edges. They were taken in his old Havemeyer apartment; he had red hair and was dressed in a patchwork coat.

“1989 through 1992 was a pivotal time in the art scene in Williamsburg. From the windows of the Cat’s Head you could see the glow of the art installations inside and thousands of people waited outside anxious and full of anticipation about what was in store inside. We were inviting young artists to showcase non-precious artwork in large, raw spaces. We wanted to encourage the artists to come out of their studios and make work that the audience could dive into, to interact with each other and explore their own creativity. We were weaving in and out of dumpsters making art out of trash. You’d see really exciting trends—you really felt you were on the cutting edge. Now if you tried to do the same thing today you’d get shut down in a second. I really appreciate being able to experience New York in the 80’s, but I left at the right time. In 1994, Henry left Brooklyn and moved to Switzerland, where he continued his involvement with the arts, and spent 10 years immersed in another bohemian art scene.

See description at end of article.

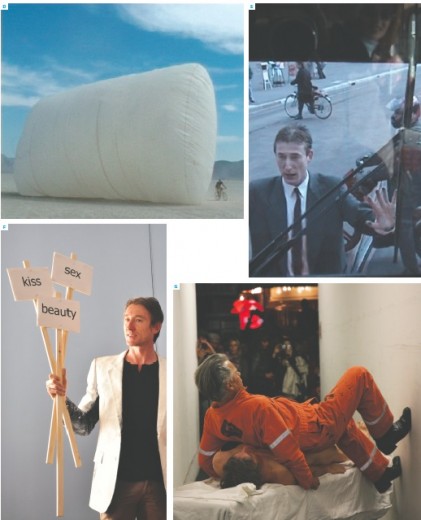

Henry was recently invited to perform at the Korean Experimental Art Festival in Seoul. After getting off the 21-hour flight, he met other artists from around the world at the airport waiting to board a bus provided by the festival organizers. For the opening night of the ceremony artists meet other artists, celebrate and drink, and find out when they’re set to perform. “You know how wild and crazy it’s going to get based on the lineup,” said Henry. During the festival, the organizers assign each artist an assistant, usually an art student, who helps gather materials for that artist’s performance: a pig’s stomach, a dress, anything needed from any of the nuanced shops in South Korea. Afterwards took park in the Jeju art festival, which he called, “the South Korean version of Burning Man but not quite as funky,” taking place on Jeju Island, off the coast of Korea, centered by Halla-san volcano, and known for its high winds. In the two and a half weeks he stayed in Korea, he performed a total of four times and built an 80-foot wind installation out of white fabric wrapped around poles.

Last year, Henry also directed the first performance art biennial ever held in Houston, Texas, called “Lone Star Performance Explosion.” It was the first time he had spearheaded a festival on this scale.

“To create a new awareness, to jolt people out of their routine—that’s the power of all art. I think the medium of performance is a potent one. The human body is the most influential material you can use. A lot of people are just stuck in their ways. I’m pretty good at creating a situation that stops peoples’ normal flow. I sometimes question if it’s a complete waste of my time, but then I see art that resonates with me and I say ‘Yeah this really can make a difference.’ You don’t have to touch every single person in a space. If you can touch just one single person, then the performance is a success.”

Henry’s performance work is often political and social, dealing with issues of sexuality, gender, how we use or value our time, and what happens when our lives are pushed from the norm with these themes. One performance, called “Time Out,” where he stops a moving trolley during a busy commuting afternoon, was developed in Prague, and in Basel and Geneva, from 2000 through 2001.Specifically timed for three minutes, one purpose of the performance is to see how valuable such a short amount of time is to another person. Dressed in a nice business suit and carrying a bag a groceries, Henry walks out in front of an oncoming tram. The paper bag rips on cue, the tram stops precisely where he wants it to stop blocking all traffic. He searches slowly—and stalling for time—gathers the carrots, the spaghetti, the lettuce, and the tomatoes, to the annoyance of the conductor and all of the passengers on board. Next, when a policeman intervenes, or when pedestrians or even the conductor start helping him, Henry looks to see if he reaches his target time and boards the trolley and hands everyone a business card that reads: “A performance by Myk Henry. What is 3 minutes of your time? Send your answer to my email.” Outside, through the trolley windows, a sandwich man walking on the street corner can be seen with a sign that reads: what is three minutes of your time? Typically there would be a crew of at least five people helping Henry.

One email response was: “You managed to steal 3 minutes of our (the passengers) time yesterday. I noticed that you had bought yourself a new suit and that you had an accomplice with a sign. For what purpose?”

The whole performance was documented by multiple cameras. It won him the La Bourse Federal, the National Swiss stipend for contemporary art, and Le Prix Contonal de Geneve, or the Geneva State prize for Contemporary Art. He was the first foreigner in Switzerland ever win the Providentia Prize (Young Art) for contemporary artists.

Erik Hokanson, co-director of Grace Exhibition Space and friend of Henry. says, “Myk can be really obsessive, pushy and can size things up accurately, and it’s these three things that make him great. He has this ability to mix social issues, political issues, racial issues, and gender politics, and squeezes them through a fine mesh so that you’re getting a distillation of all these ideas with a beautiful perplexity. He’s so conceptual, and it can be very literal, but it’s this intensity of purpose which keeps you continually focused on his actions.”

Henry has a lot of documentation of these performances on DVD’s, few of which can be found on the internet. He has neither an artist website, nor a dedicated Vimeo page for his performance work. Only a listing on apartmenttherapy.com about his work as a renovator can be found, where clients talk about his jobs installing a French door, a loft, a kitchen, renovating an apartment in the West Village, the Upper East Side, or repairing buildings by the Fulton Fish Market.

“If your project involves anything with wood or metal and needs a clever eye and a master’s touch, Myk is your man,” wrote one client. “Myk expertly rebuilt my closet the other day. He does what he says, charges fairly, and left my apartment in excellent shape. He also happens to be a very interesting, thoughtful fellow, an unexpected fringe benefit.” wrote another. From “I got this out of the whole deal,” he said, pulling out a sword from its sheath, and brandishing it in his dining room. He had just come from a Hurricane Sandy-related flood, and a client was throwing away a pile of old rusty antiques. Henry said the tenant gave him the old sword, an Arabian looking weapon, after he finished the demolition job.

His adeptness of being a renovator comes from his experience at building art installations. In the Warehouse Scene, he was a construction coordinator, and his skill developed further working on a construction crew. “It was stimulating to be part of a young team,” he said. “I’ve always been handy, and I’m really good at it now. I’m able to pull things together that others couldn’t even dream of doing. I can make the unimaginable happen and make it all look professional. How do you figure this stuff out? How do you make this picture in your head a reality? How do you transform your dreams into reality?”

At press time the WG learned that Henry’s next project is organizing a multi-city North American Performance Art Festival. In June and July, a group of performance artists from around the globe will bring live art to audiences across the USA and Canada, traveling in an old school bus Henry proposes to convert into a mobile command pod.

Rent me

Park of the Future, Amsterdam

April 1999

As many as two million people are feared to have perished in North Korea since food shortages swept the country in the mid-1990’s with refugees and aid officials on the border painting a picture of a society in desperate straits. Their countrymen are therefore turning the women and girls of North Korea into merchandise to be traded for food and money. There is currently a widespread shortage of women in China and it seems that there is an increasing number of young North Korean women, many in their teens, being smuggled out of the country and sold to Chinese farmers as brides, so that familiescan eat. (The Herald Tribune February 1999)

The intention with the performance rent me was to highlight the situation in North Korea by placing myself in the Park of the Future shop as the merchandise. I was not for sale outright but could have been rented by any individual for the duration of one month. As a means of initiating a slave trade I rented myself without conditions.

The only stipulations were; a sum of 15,000 Euros was to be paid as a rental fee, the rental agreement would be for one month, and I would have the right to document whatever took place during this period of time. Beyond this the renter had complete freedom to do whatever he / she pleased with me during this time.

The 15,000 Euros was to be donated to an international aid organization working in North Korea.

Note 1: Many people were curious and throughout the day posed a wide range of ethical, political, racial and financial questions. One offer was made to rent me by another performance artist but this turned out to be a hoax.

Note 2: Some of the questions asked were as follows:

I have some financial problems with a business deal at the moment. If I was to give you a gun could you go and shoot somebody for me? If I gave you 15,000 Euros could you to go to Korea and bring me back a teenage girl?

What gives you the right as a white western male to represent a situation here in Europe which is actually affecting young Asian girls in the far East? Why don’t you go there and dosomething about it?

Has anybody offered to buy you?

Leave a Reply