Massive icebergs photographed in Greenland. PHOTO BY JAMES BALOG / EXTREME ICE SURVEY

What does the overdevelopment of Williamsburg/Greenpoint have in common with melting glaciers? Fossil fuel, that’s what; one’s using it, the other’s choking on it. Well, we’re all choking on it.

CHASING ICE

Jeff Orlowski

Submarine Deluxe Presents An Exposure

Production in Association with Diamond Docs

James Balog, a fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers, was trained as a geo-morphologist, but felt computer models and statistics weren’t going to tell the earth’s story in a way people could understand. He took up photography and created seductively gorgeous books on things like endangered species, and, most recently, ice, to bring home to you and me some very nasty man-made doings on the planet we inhabit. Initially a global warming doubter, Balog changed his mind in Iceland when he fell in love with the “alien beauty” of ice, and was shocked to learn the massive Solheim (Sun House) Glacier was melting at an alarming rate, and that this frightening level of shrinkage was largely our own fault. The bad guy in the story: greenhouse gases. Namely, human generated carbon dioxide released into the air via burning fossil fuels (among other culprits).

Are the massive high- and low-rise developments, both proposed and built, in Williamsburg-Greenpoint employing alternative energy sources? Are solar or wind power, or biodegradable and renewable fuels used at all? Or are good old, business-as-usual, earth-warming fossil fuels heating and cooling, running elevators, cooking dinners, freezing ice cream, doing dishes, and washing clothes? Is there any concern on the part of the city or the developers for the melting glaciers?

Who cares if they melt? I’ll never get to see a stunningly blue iceberg the size of Staten Island. No, but I can go to Staten Island to see what Hurricane Sandy delivered as sea levels rise and “rare” storms become less rare, and more violent and costly.

And why is that? Partly because when glaciers melt, the water has to go somewhere. I picture it as a martini glass full of ice, sitting in a soup bowl of water, sitting on a plate. Normally (or, the old normal) ice melts and refreezes seasonally. That’s how it’s been for longer than you and I can imagine. But let’s say heat-trapping gases like CO2 melt too much ice, and winters aren’t cold enough, and summers are hotter and longer, and you have even more melting, and all that excess water starts to flow. So? So the melting ice overflows the glass into the bowl, which reaches capacity and overflows onto the plate, which represents the world’s coastlines. If the bowl is sea level and it rises past capacity, Chesapeake Bay, the Gulf Coat, the Ganges River basin (forget islands), lower Manhattan, the Brooklyn coast, Long Island, Staten Island, the Jersey shore, and on and on are washed away under the sea. And if we don’t fix it, the people living on coastlines go where? That would be a lot of displacement.

Scared yet? We all should be. Nah, forget it. Mayor Michael Bloomberg is pleased; we should all be thrilled to be living in the greatest city in the world, freely burning all the fossil fuel we want. I hate to break up the party.

Balog decided to record the astonishing rate of glacial melt. Jeff Orlowski’s documentary about Balog, Chasing Ice, is as beautiful as it is unnerving. Balog: “I had this powerful idea that the most powerful issue of our time was the interaction of humans and nature.” How could he photograph climate change? He formed the EIS, or Extreme Ice Survey, to record the dying glaciers. Cameras with computer chips and timers, in housing built to withstand outrageous weather conditions, were mounted in Iceland, Greenland, Alaska, and Montana, and the recording began. The results should ruin your day.

“I didn’t think humans were capable of changing the basic physics and chemistry of this entire huge planet,” says Balog. But records of ice cores tell us just that, like rings on trees. Bubbles of ancient air trapped in glacial ice cores measure the amount of CO2, which is now an astounding 40% higher since man started adding to the heat—40%. One glacier that took 100 years to recede ten miles took ten years to recede nine miles. Running for the hills yet?

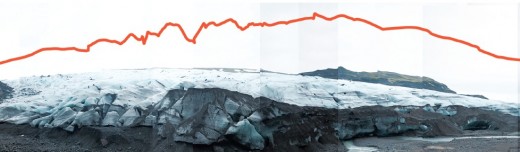

The Solheim Glacier in Iceland in February 2009. The line

represents how much the glacier changed in nearly three years.

PHOTO BY JAMES BALOG / EXTREME ICE SURVEY

By the way, this means the chemistry of the air we breathe is changing, too.

The documentary takes a breathtaking look at some of the wildest parts of our planet. It seems reassuring to think humanity hasn’t touched everything. Well, it was reassuring. Balog is a messenger many still want to ignore. The film opens with news clips of recent natural disasters, most weather-related: more-frequent tornados, hotter and more-frequent forest fires and droughts, and bigger, badder hurricanes. The clips are followed by climate change skeptics, including Sean Hannity of Fox, Glenn Beck, and Weather Channel founder John Coleman. Says Balog, “We as a culture are forgetting that we are actually natural organisms and that we have this very, very deep connection and contact with nature. You can’t divorce civilization from nature—we totally depend on it.”

Filmmaker Su Friedrich keeps track of over 100 new developments in the space of a few years. PHOTO COURTESY GUT RENOVATION

GUT RENOVATION

Su Friedrich

Outcast Films

Indie filmmaker Su Friedrich records a different kind of melting in her documentary. Instead of displaced glaciers, humans melt away from rezoned neighborhoods.

Friedrich moved to Williamsburg in 1989, into a loft building that had been abandoned for 20 years. The landlord provided two space heaters and a water line. Friedrich and her partner and friends did the rest, literally making homes and studios from scratch at their own expense. They were given a long-term commercial lease, which meant commercial-rate taxes and illegal living. For years the city looked the other way as artists moved to industrial areas in search of cheap live/work space—spaces not intended for habitation. But Manhattan—the great cultural mecca—had become hostile terrain for artists as rents steadily climbed.

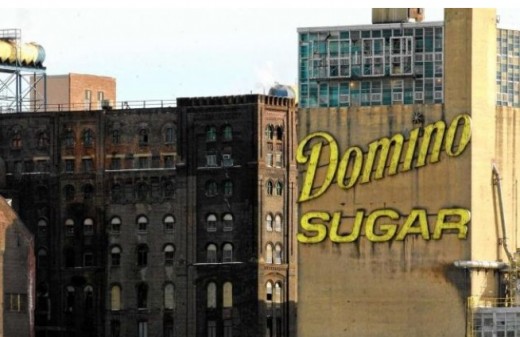

At the time, Williamsburg was a going industrial area. The Domino Sugar plant was a huge employer. And there were zipper, glass, and plastic bag manufacturers—a long list of mostly light manufacturing, not all of it healthy to live near. The community was working class. Many people walked to their jobs. Artists coming in changed none of that: no zoning re-maps or jumps in rents. Local businesses were supported and life went on. People like to say artists begin the gentrification of a neighborhood, but it’s what—or who—follows that damages a way of life. Friedrich’s loft looks like it was cold in winter and hot in summer. There were few amenities, or trees, and scant social services. No one would have called Williamsburg pretty or desirable back then, but it was stable.

But the city had its eye on the Brooklyn waterfront. There was a lot of waste. The East River shoreline was largely inaccessible, much of it weedy, garbage-filled wasteland behind chain-link fencing. A survey was conducted and “industry in Williamsburg was declared moribund.” Friedrich says that was a lie. Isabel Hill was a city planner at the time, and she resigned, according to Friedrich, over that misrepresentation. Hill’s film (highly recommended), Made in Brooklyn, documented the fact that industry was alive and well in Williamsburg in the 1980s and ’90s. The area, she says, held a key ingredient to any successful city: diversity. A functioning industrial zone is also a healthy source of tax revenue.

The skyscraper The Edge in progress, overlooking Gilbert Cass building in renovation. PHOTO BY LINDSAY WENGLER (COURTESY GUT RENOVATION)

Friedrich kept a chart of the demolition and renovation of a 15-by-6-block area, from North Williamsburg to Broadway. The changes were rapid and wrenching. Across from her loft were a forklift repair company and a bus repair garage. Not everyone’s ideal neighbor, but not a problem either. The facilities were slotted for demolition; the jobs went away. Diversity could have been preserved, but the drumbeat was for luxury living on the river.

Realtors smelled blood. Hipsters had arrived, and with that influx serious change came to the community. Families sold buildings for deals that would have only gotten sweeter had they held on. Factories were sold for their real estate, and demolished. The 11-acre Domino Sugar plant sold for $55 million. Thus began an urban diaspora of mostly working and lower middle class families. It took a little longer to dislodge the artists.

In 2005, the area was rezoned residential, a “businessman was in power,” and investors and developers were handed Williamsburg, carte blanche, to recreate. Upland was to be protected from the high-rises that began to loom over the East River skyline. A pattern of rip down and rebuild began at a furious pace. Friedrich records much of this, talking to workers and business owners. A car repair service given notice, a carpeting warehouse gone, a soap and candle manufacturer disappearing; the list goes on.

And, Friedrich asks, why wonder that labels no longer say Made in the USA? The butcher shops on Bedford Avenue went; the bakery (a bread bakery, not a café-bakery), old taverns, the shoe repair—small businesses that served the community—disappeared, replaced with endless bars, cafés, galleries, and, eventually, boutiques with overpriced dresses. Williamsburg had become the new nirvana. Builders and dwellers were lured by promises of the hip life one stop out of Manhattan. Or was it the tax breaks on luxury condos?

The city could have—and has—grandfathered-in commercial lofts for residential use in cases of longstanding residence, particularly for artists. The Bloomberg administration wanted none of it, ruthlessly serving the needs of fortune-hunting developers that were all but rubber-stamped by the City Planning Commission. Rents in Williamsburg became outrageous, and condo prices hit the moon. A tiny percentage of affordable units were a requirement, but the definition of affordable was not truly reflective of the AMI (area median income). The mayor boasted recently that people are voting with their feet: arriving in New York, and Brooklyn in particular, in record numbers. I would ask, what’s so good about overcrowding, and gigantic glass and steel dormitory apartments?

There’s an amusing scene in the film about a giant rock dug out of the newly emptied lot across from Friedrich’s loft; it took weeks of power-tooled attempts to break up and remove. A more creative builder or architect might have made the mini-boulder a centerpiece or a play area for kids. Kids! Play area! We’re talking cost per square foot, and profit, not the imaginative life.

Friedrich finally left her home of 20 years, booted out by progress. Her wry humor and healthy anger lend a warm tone to a tough tale. By the time she gave up, she’d endured two years of pounding and banging as old buildings went down, and generic, look-alike apartments with subzero fridges, mezzanines, and Juliette balconies went up. It’s getting harder and harder to tell where you are anymore in Williamsburg.

GRINGO TRAILS

Pegi Vail*

Zebra Films

This very worthy, yet to be released documentary focuses on remote settings beset by backpackers. Instead of an urban invasion of developers, adventure travelers invade the wild, leaving a footprint that can’t easily be erased.

In 1981, a young Israeli backpacked with two friends and a guide into the uncharted Bolivian Amazon jungle, in the Madidi National Park. He was separated from his friends in a flood along the Tuichi River and was lost for 26 days. Local villagers helped in the rescue, and against the odds he made it out in one piece. He then wrote a book, inadvertently encouraging a trail of backpackers looking to recreate his experience. Why? It was a harrowing experience, but it had the thrill of the new, and the promise of excitement off the beaten path—sort of Indiana Jones meets hippies in the Amazon.

At first it was just a few backpackers—a young, mostly Israeli and European crowd, with not a lot of cash, but with the security of available money in an emergency. Pretty girls traipse the jungle in jeans and tank tops, their hair glossy with natural ingredients; boys are scruffy and carefree. Backpackers are low maintenance. They need water to brush their teeth, some food, beer, and a place to crash. But, like the artists in Gut Renovation, backpackers carve trails to unexpected locations and a hidden world opens up. You could say the first few backpackers are the pioneers, who, once back home, tell a friend, who tells a friend, who tells another friend, until the secret is out. And suddenly a place no one knew about sprouts hotels and bars and pollution. Where there were huts and a simple—if poor—life in tiny villages, a town springs up looking like old Key West. One Bolivian area with a single hotel has seen 45 built in a very short time span. An economy appears where none had been, a chance to exploit a natural resource, and to test an ancient ecosystem that is no match for modernity.

Backpackers don’t like to see themselves as tourists. Touring is what moms and dads do. But, as sociologist Erik Cohen says in the film, “Backpacking to back packaging becomes a sub-specialty of institutionalized tourism.” Stuff to accommodate a backpack boom gets built without civic planning or infrastructure. That’s everything from potable water to bathroom waste.

Similar scenarios played out on remote islands of Thailand. But here you can add hedonism into the mix, as beaches like Haad Rin on Ko Pha Ngan Island became the scene of full moon parties that are not much more than debauched frat parties gone native. Fifty thousand backpacking fun lovers welcomed the new millennium on the small peninsula. In the morning, the beach was littered with drunks, plastic and glass bottles, and “fuck buckets”—beach pails full of Sing ha, Coca Cola, and Red Bull (or vodka—or whatever), with multiple straws to sip from all night, into the dawn hangover.

Costas Christ, editor-at-large for National Geographic Travel, is now a sustainable tourism advocate, but he was one of the first backpackers to discover Haad Rin. He let the secret out, to his regret, after stumbling onto the then-pristine beach while trying to get away from backpacking mobs. In the film he asks, “What is our environmental impact? Tourism is selling nature and cultural heritage.” In an economically challenged area, one rich with natural beauty and a singular culture, how do you strike a balance between economic opportunity and that culture and its environment? Do you come in and trample, like the backpackers in the Bolivian pampas, where the anaconda is endangered by such trampling? One kid reaches out to touch the huge snake slithering through the mud to get away. Asked why, he says he doesn’t know. “Because I could?” The native guide tells him they must not touch; the mosquito repellent on their skin is toxic to the snake.

Gringo Trails overlaps with Chasing Ice as witness to the mindless march of so-called progress. Is civilization still civilized if it destroys more than it creates? Or if what is created serves no long-term, sustainable purpose? The overlap continues in the current development of Brooklyn—overbuilding without considering energy sustainability. Is this still progress? Progress to what end? These questions don’t seem to get asked. Rolf Potts is a travel writer interviewed in the film, and he’s seen it all: “As travelers we seek authenticity so desperately that host nations will stage this. The dislocated middle class people look to the poor for this, [for] a National Geographic moment.” How ironic is that?

The tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan has taken a very strict approach to tourism, and backpackers are not welcome. The charge is $250 a day to visit, food and lodging not included. The affluent, Hollywood, retired professors are welcome. If you don’t learn the etiquette, you are welcome to leave. As the documentary makes clear, Bhutan is interested in its GNH—Gross National Happiness—ahead of its GDP; progress is very slow and very conscious. Wonderful, but sad, too, that only the elite can visit.

What is striking about all the natives interviewed in the film’s many varied locations is how soft spoken they are. The idea of a free-for-all, of the laissez-faire tourist loudly doing whatever he or she wants, may be waning, and the idea of all of us as guests on earth may be taking hold. I wish Brooklyn would look into sustainable development. Wait, that’s the job of the City Planning Commission…

Back to Indiana Jones. The actor who played him, Harrison Ford, has been a spokesperson for Conservation International for fifteen years. CI encourages ecotourism, sustainable economic tourism, and biodiversity. Maintaining the rainforests for the sake of the air we breathe is the actor’s particular concern. He points out that we are visitors during our short tours here; we don’t own the earth. Right. It’s not a party, though there’s no reason not to celebrate. Or, as the movie star says, “People need nature, nature doesn’t need people.” Would it kill us to show a little appreciation? It might kill us if we don’t.

Pegi Vail is a longtime Williamsburg resident who is also an anthropologist. Her dissertation, being published as a book by Duke University Press, compares the gentrification of Williamsburg and the artists’ role to the role of backpackers in Bolivia. She filmed in Bolivia and Thailand.

THE DOMINO EFFECT

Megan Sperry, Brian Paul, Daniel Phelps

The Domino Effect Movie, LLC

The idea that cities need urban planning commissions to think long-term sustainability, diversity, and land use is one of the key lessons of The Domino Effect, a lesson—alas—gone largely unheeded. Movie director Martin Scorsese recently petitioned New York’s Planning Commissioner, Amanda Burden, to protect the Bowery from overdevelopment, the part of Little Italy where he grew up. The East Bowery Preservation Plan calls for limiting heights to 85 feet. I wish them and him luck.

No movie personality has spoken out for Williamsburg- Greenpoint, just an overburdened local citizenry. The Domino story starts with the 2005 rezoning and ends with that citizenry being pretty much duped. During the 2005 rezoning, the City Planning Commission promised the Domino plant would remain industrial. The Sugar House, as the locals called it, refined sugar for nearly 150 years. After the Civil War wrecked manufacturing in the South, the Domino refinery took over and became the world’s biggest producer of sugar, right here on the East River. The plant shut down production in 2004, causing a mass exodus of jobs.

Community Preservation Corporation Resources (CPCR) purchased the sprawling site with plans for towers of luxury housing and 30% set aside for “affordable” housing. In testimony before Community Board #1, CPCR spokesperson Susan Pollack stated in no uncertain terms that, “Our company’s mission is to build affordable housing and stabilize neighborhoods. That’s it, that’s the mission for 35 years.” The neighborhood already was stable, but affordable housing was indeed needed. The trouble is that profit was CPCR’s real motive; the affordable component was, well, sugar to sweeten the deal, to, in effect, divide the community with a promise of housing if zoning could be radically changed for the Domino site. The argument was that affordable units could be paid for by the luxury condos. Read: big bucks pay for crumbs that the working class can pick up.

The mayor and the Planning Commission were all for it, whatever it took, however high, no matter an unprepared infrastructure with insufficient schools, a subway line already stretched to bursting, and a neighborhood with some of the lowest amount of open park space per capita in the city. In 2002, newly elected Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg declared— almost by fiat—“a new housing marketplace targeting residential rezoning.” That’s 10,000 units of new housing. According to the documentary, not since the 1950s has New York City seen such radical change.

If Su Friedrich tells the personal story of a community in upheaval, The Domino Effect talks to affected locals, to the history and economic impact of that upheaval. Since 1997, Williamsburg-Greenpoint has lost half its jobs. The area went from diverse employment to a service economy. That’s progress? Manufacturing and related jobs average $16,000 a year more than retail or restaurant work. And service jobs are usually dead-end jobs needing minimal skills. But, the mayor said in a radio interview, because they generate jobs and tax revenues, “We love rich people.” Here’s another catch: to attract developers to Brooklyn, huge, twenty-five-year tax abatements were held up as carrots. Who makes up that lost revenue? The rest of us.

Local resident and activist Dennis Farr said, of the “wholesale slaughter” of Williamsburg as he knew it, “Whenever you have a bank involved you have to pause; when you have a consortium of banks, you have to do more than pause, you have to interrogate.” No one interrogated Domino’s real motives as they were handed all the zoning changes they asked for, including the everywhere-else-in-the-area upland protection. They could go as high as 36 stories on the river and at least 16 on the small upland lot that was once the factory workers’ parking. The planned structures dwarf the Williamsburg Bridge; they dwarf the low-rise character of the neighborhood; and, as a side effect, they promise ever more crowding, despite a promise of four acres of badly needed parkland.

Longtime resident Manuel Zuniga wonders where “regular” people are going to live. Where once landlords were happy to have tenants, and rents were reasonable, rents became jacked-up on older buildings, while new apartments were untouchable for local residents, especially with an asking price equaling 60% of income. The film holds a shot on a sign: “Welcome to Hardcore Luxury.” Families began to squeeze in together. If you bought into the hip ‘Burg, or rented and had trouble paying the bills, you buddied up with multiple roommates. Zuniga didn’t think he could afford to stay. He began to join protests. Regular people, he said, were beginning to question the profit, profit, profit motive, to question their leadership. The crumbs on the table would go to only a handful of the thousands of low-income earners in need.

Resident Diane Jackson, once an employee of the Sugar House, talked about those crumbs: “It’s for the rich, by the rich.” As for leadership, she points out that the same vote that brought them into office can vote them out. Our elected officials have not protected our community. Says neighborhood activist Phil DePaolo, “Politics, lobbying decides; not land use.”

Does the city demand high-rise developers use alternate, renewable energy sources? Is it even in the discussion? Not a peep from CPCR about environmental protection and long-term energy sustainability.

It’s all moot anyway. The footnote to The Domino Effect is that CPCR flipped the property once the coveted rezoning was in place. Many of us warned of the possibility, practically begged the Planning Commission to make the radical zoning changes contingent on CPCR as the project developer. Not even the biggest selling point of all, the one that duped so many poor folks and divided the community, the sacred affordable housing cow, was legally binding. CPCR walked away with all the cookies.

And then they sold to Two Trees Developers for $185 million, rezoning included. Two Trees principle, Jed Walentas, held a meeting recently in one of our enlightened establishments, The Woods bar, to let residents in on his plans. He’s a pale, unhappy-looking guy with an air of knowing what’s best for the rest of us. He let us know he was going to create a community, that he understood what it takes. Some of us scratched our heads, since we were standing in our community, listening. Asked what guarantee he had to offer that he wouldn’t flip the property [again], he said, “My word.” He’s got his Zuckerburg hoodie look, like he doesn’t have more change in his pocket than most people in the world will see in three lifetimes, and a world-weary tone (or was he just weary of us little people?), so his word must be good. Right?

CPCR gave their word, too.

Rumor has it Mr. Walentas will develop the upland site and flip the waterfront parcel. What’s to stop him? He had his architect with him to explain why their buildings would have to go even higher than CPCR’s plan (partly because they’re adding two more acres of waterfront parkland; but if you add the thousands of new residents they will bring in on top of an already park-starved citizenry, it cancels itself out). They’ll keep the affordable component, but, as Walentas said, they paid a lot of money, and they are going to make good on their investment. Donut holes are inserted into the proposed new buildings for light, to help with the shadows cast by the behemoths. It all looks very downtown Dubai jazzy. Two Trees may mean well—well, less unwell than CPCR—but when a pretty blond politely, sweetly asked about green architecture, there really wasn’t an answer.

Maybe The Domino Effect needs a sequel?

WHAT’S IT ALL MEAN?

To sum up these often-eloquent documentaries: say you and some pals backpacked in to see your favorite glacier and found global warming melted it to a pile of rocks, so you go home to find you’ve been priced out of your nabe and they’ve torn down your abode and put up something glass and steel, and nothing looks the same and you think maybe you got off at the wrong stop cause you don’t recognize the skyline or any of the people under it, and your friends are all displaced and you can’t figure why your USD doesn’t go as far, and you don’t know where you’re gonna live, yeah-yuh. And you find out the high-rise crowd has taken it all and they call it progress, or did they mean profit, and you start to cough from the air, and how come so few have all the cards and cash, but they’re not putting back? Not jobs, either, and not to mother earth. No sustenance; just take, take, take till you wake in a cold sweat and say you’re mad as hell and not gonna take it anymore. So you scrape up some funding and some crew and make a documentary to say yeah-yuh: save it or lose it. That means even you, Mr. and Ms. Billionaire, because nature couldn’t care what’s in your wallet. ?

Janyce Stefan-Cole is a longtime resident of Williamsburg, and is the author of Hollywood Boulevard (Unbridled Books).

Leave a Reply