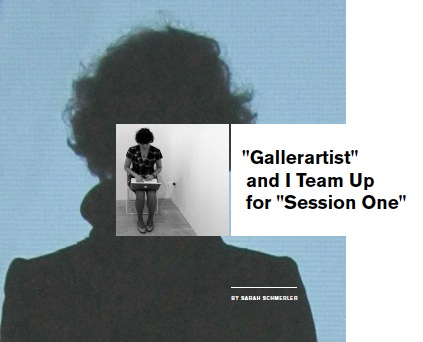

“Gallerartist” Austin Thomas, and her shadow image, at the first Pocket Utopia Gallery. Gallery image photo by Catherine Bindman

What’s the role of the art gallery in the 21st century? Why are some artists successful, while others spin their wheels, forever seeking career satisfaction? For Austin Thomas, artist and owner-director of Pocket Utopia Gallery, the art world is a kind of ecosystem, and we are all viable elements within it, sustaining it and make it whole.

In this intimate conversation with Thomas that took place at Pocket Utopia—the gallery she started in Bushwick and then moved to the Lower East Side—you’ll glean some of the answers. Full disclosure: Thomas and I are recent collaborators; on August 4, we conducted a mind-blowing, four-hour lab session with nine artists called “Session One” of “Pocket U-niverse-ity.” To put it simply, we felt we could forge a radical anti-grad-school form of collaborative learning whereby an art gallery serves as the hardware, the art market serves as the software, and the artists provide the content.

So, what really ended up happening?

That night, Thomas sat the nine participants down and, after oiling them up with some beer, casually informed them: “I’m giving you a show here at Pocket Utopia. One work each, from all of you. You are the group that will inaugurate my fall season. I’m calling it ‘Session One’ and it opens September 8.”

I went on to lecture on phenomenology and teach a short writing seminar. I also talked about radical art historian Aby Warburg, and what sets one group show apart from another.

After dinner, (yes, Thomas gave the artists dinner, as well as a show) we were still stunned, so we did shots of Johnny Walker Black. No one expected a gallerist to put their money where their mouth is. No one.

At the time of this interview, Thomas had just completed studio visits with all nine artists.

SARAH SCHMERLER: Give us a little background. How and where did you start Pocket Utopia?

AUSTIN THOMAS: Pocket Utopia started in 2007 in what is now called “Bushwick,” but it wasn’t known as Bushwick back then, and I think that’s important. It was called East Williamsburg. Anyway, it opened as a storefront gallery, salon, exhibition, and residency project—and it was all those things.1037 Flushing at the Morgan Avenue L Stop.

Author Sarah Schmerler, not in mid-lecture, likes to dance.

Photo taken at Waacktopia Party. Photo by Lina Jang

SS: What sorts of galleries were surrounding you at that point?

AT: English Kills had just opened, and there was another space called Ad Hoc, on Bogart Street—a silkscreening, street-art gallery. When I came in, Pocket Utopia was like an extension of my artwork, like a social sculpture; it had a very contemporary bent. I officially opened with a show of 22 artists from the Pierogi Flat Files in Williamsburg. It was very deliberate.

Tell us more about what you mean by “deliberate.”

I wasn’t just showing my friends. Pierogi had been a very active community-building gallery in Williamsburg, but with a serious agenda, and I wanted to respect that tradition and kind of pay dues and open up in a new artist neighborhood. I had been making art myself in that neighborhood for seven years, at other studio locations. I had built some major commissions—one for the Public Art Fund at 983 Flushing, where the Life Cafe was later, for instance.

What sort of work were you making. Was it sculpture?

I called them Perches; they were social sculptures for people to sit on. I made one for the Drawing Center, the Public Art Fund, Smack Mellon … they were elaborate benches made out of wood, almost like backyard decks for an urban environment—part architecture, part social sculpture.

Are you still making Perches?

I’m working on one for the City right now, under the Percent for Art program. It’s going to be in East Williamsburg, proper, in front of the Morse Street Market, slated for spring 2014. It’s only blocks away from where Pocket Utopia used to be. So I’ve really come full circle.

Can you tell us more about how you envisioned running a gallery? How did you get your bearings?

I opened Pocket Utopia because I wanted to push my ideas beyond making structures. The first Pocket Utopia was a place for artists. I was an artist, I was making work in the neighborhood, and I thought: I’ll open up a space and call it Pocket Utopia as a way to work with other artists and their Ideas. The site was an old barbershop that I rented for two years and renovated to create a white gallery space. I got a loan from my mom to do it—$10,000—so of course I showed her work. My mom is just like every other artist: “When’s my show going to be?”

Your mom’s an artist?

Yeah. I gave her a retrospective. It covered her work from her glory days in Greenwich Village in the late 1950s to the present. It was called Kayosities, and it was a tribute show to Kay Thomas, Cabinet of Curiosities, including her journals and brushes and photos from the Village. It’s all true! My tagline at the time was: “Pocket Utopia is a relational exhibition salon and social space run by artist Austin Thomas.”

Okay, so there’s a little pre-history there. How did you transition to the Lower East Side?

After mounting 20 exhibitions in Bushwick, I closed there in 2009 with a group exhibition of local artists called Finally Utopic. I opened on the Lower East Side with very strong encouragement from C. G. Boerner, a gallery on the Upper East Side that shows Old Master prints, and I started to collaborate with them. The man who runs it, Armin Kunz, and I are old friends, and we reconnected because he started to collect Bushwick artists, including my work.

You mean he came to Pocket Utopia?

No, he’d never come to Pocket Utopia, but he knew my work, and when Bushwick became an art neighborhood, he went to Famous Accountants and bought a Matthew Miller from that show. I’d reached a point with my artists that they needed to expand their careers, and I needed to find a way to get to the next level as a gallery and sustain my operations. I started handling Miller; Boerner produced my catalogue for that show, and they, in turn, showed his work uptown. I showed Old Master prints downtown. We wanted to deepen the conversation, bridge the gap between Rembrandt and Bushwick.

There’s a huge art history there; let’s make that history deeper. Flow. That’s a very key word for me. Flow: I’m still an artist, and I see it all as a collaboration. I see myself as learning through teaching.

Hence, “Session One.” Did you see the “Session One” artists’ faces when you gave them a show? It was like they were caught in G-force!

[laughs] Yes.

So here’s a mean question: Do you think artists on some level prefer to sabotage themselves? Do you think they’d rather sit on their bar stools and cry into their beer rather than understand what it means for their gallerist to pay the rent and really represent them?

Yes, but let me explain. When I began Pocket Utopia in Bushwick, there was a lot of what I call “back patting.” There were no desks, so we sat on the floor. We talked about ideas, and that was a very good thing for the neighborhood.

When artists sit and talk about ideas, it builds ideas, it builds encouragement. Soon, in Bushwick you saw lots of other spaces opening. The whole neighborhood became viable from artists sitting around, patting each other on the back; it’s a very lively place, that sort of environment of encouragement. And art comes out of that place.

But a gallery is different—at least a gallery at the next stage, your stage?

Artists always underestimate their audience. They call this thing “the art world,” but I call it the real world. And the real world is full of culture, and ideas, and there’s rent to pay. You need to think about the real world as your audience.

So how do you, as an artist and gallerist, keep it real, so to speak?

Via projects like “Session One,” for instance. By looking to gallerists who kept afloat in the past and seeing how they managed. Holly Solomon—I think about her a lot. She opened her space, and Gordon Matta Clark encouraged her. There were a number of artists in Soho at that point that needed commercial representation. I see my artists as co-creators with me of this business, and I am co-artist in their representation. And together, we are expanding our audience. Solomon’s artists were at a point where a little clique would not sustain them.

Tell us more.

In 1977, Solomon represented her artists at the Basel Art Fair with a show called Pattern and Decoration. 1977. I read about dealers like Paula Cooper, Arnold Glimcher, and I see there a bigger cultural conversation that is really important, a conversation that makes the world a better place. It gets us over our sort of idealistic, rosy eyed—barstool—view and throws light on how ideas can be expansive to community. Ideas are like a beehive, like a super highway, and for our planet to survive we’ve go to be on this road together.

Okay, so what I’m getting here is that artists needs to expand out of their comfort/beer/back-patting zone for their work not to get stagnant, and a gallery has to…what? Develop new audiences in places and ways that artists might not initially comprehend?

After two years, artists who run galleries often just get burned out and return to their studios. And that’s it. I’m seeing if I can sustain beyond two years. I’m selling to collectors. I’m probably going to have to think of doing an art fair, like at Salon Zurcher. I’m doing “Session One” with you, and that’s important.

Wasn’t it you who said that the gallery model isn’t working for artists?

Yes.

Wasn’t it your phrase, how we need to “open doors”?

Yes. The way I see it, it’s like I’m this Joseph Beuys character, and I’m collaborating with you, and we have this group of artists, and we hope that this first “Session” with them will tell all of us something—about Time, Color, about art right now. We hope—I hope—that it’s all contextualized within this group, in a very concentrated space. We limited the participants to nine artists, and it’s about focus, about looking at this context close-up. It’s like Finally Utopic, that last show I did in Bushwick, only it’s a beginning. We are going to take on these issues that you and I care so much about—the role of the gallery, the failure of grad school, the way artists don’t act in their own best interest—and do it through gallery representation. And maybe make a breakthrough at the same time to expand these nine artists’ careers, and we’re going to co-expand. And…Oh, Jeez!!

What?

I realize that, technically, what I want to do is something that can’t be done!

Wow. Is this the point where we should both pat each other on the back and have a beer?

No. We’re just going to head into the unknown and do it. In Bushwick, my rent was $600, and now I’m paying something close to $2,000—four times as much—every month for the next year. My mom (whom I paid back, with interest, incidentally) didn’t give me a loan this time. That means you and I have to think four times as…

Big?

Just wait until “Session Two”!

“Session One” opened September 8 and runs through October 13. Nine artists, from neighborhoods ranging from Bushwick to Montclair, NJ, who signed up for what they were told would be “a unique learning and exhibiting opportunity,” participate: Nate Anspaugh, Joey Parlett, Danielle Dimston, Bara Jichova, Shaw Osha, Debra Ramsay, Aimee Hertog, Krista Svalbonas, and Laurel Lueders.

Leave a Reply