Generations – Two Stories from The Moth Book

“The Moth is an acclaimed not-for-profit organization dedicated to the art and craft of storytelling…. Since its launch in 1997, The Moth has presented thousands of stories, told live and without notes, to standing-room-only crowds worldwide.”

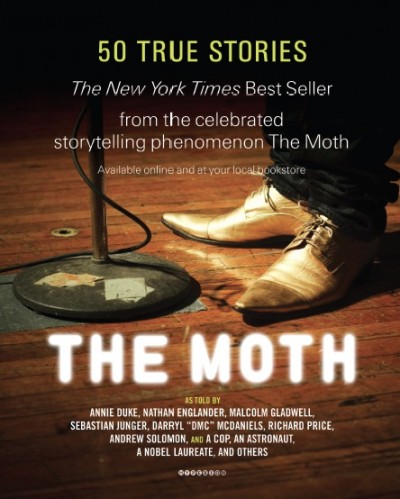

“The Moth – 50 True Stories” is a selection of those stories recently adapted for print and published as a book by Hyperion. The Moth has generously given the WG News + Arts permission to reprint two selections: one by Marvin Gelfand who lived in Williamsburg in the first part of the 20th century, and Ellie Lee, a Chinese immigrant from Hong Kong. The theme they share is “Generations.”

Moth StorySLAMs take place almost weekly in New York City—open-mic storytelling nights, where anyone can put their name into a hat for a chance to tell a five-minute story on a theme. The Moth also presents a monthly Mainstage show, during which storytellers share ten-minute stories that have been crafted with a Moth director.

The annual Moth Ball, the biggest event of the year takes place May 13th. To purchase the book and for a full schedule of events, visit themoth.org.

MARVIN GELFAND

Liberty Card

My story goes back sixty-two years, to the autumn of 1940. I won’t fill in the blitz and Wendell Willkie running against FDR for the third term. The story, such as it is, took place in a sprawling borough by the sea, Brooklyn, in a neighborhood tucked into the northwest corner on the East River, known as Williamsboig, to distinguish it from Williamsburg, the colonial restoration.

My parents were very late immigrants to the United States. My mother came with nine siblings in 1930. My father had come in the 1920s, it seemed—that side of the family never disclosed much. I have a feeling he did something infamous, because World War I was involved, and the borders changed, and then there was the Russian Civil War and Lenin attacked the Poles, and you know, God it was terrible. Who knows what people did to survive?

But he never told stories like Herbie Kleinman’s father, who was a baker with a baker’s great belly. You know, “I sewed jewels into my underwear and snuck out of Odessa!”

So they married and settled in Williamsburg, where my mother’s family lived, where the Satmar live now, the very pious Jews. My family was not pious in that energetic way.

We lived in the part of Brooklyn that had row houses, not A Tree Grows in Brooklyn Williamsburg—Betty Smith’s Irish tenement Williamsburg—but a row house that had been lived in by the Brooklyn bourgeoisie. It had been broken up into not floor-through apartments, but half floor-through, and we lived in a succession of them.

I was overprotected. I was treated as if my parents had had a child before I came along … and that child had died.

My parents had come here as much out of fear of what had happened as what was happening, and what was likely to happen in Europe. They escaped the worst of it, but there was a mixture of hope to be sure. America was called the Golden Medina, and there were so many great success stories: David Sarnoff, Eddie Cantor, you know, I could run the list now.

But their fears were great. My father worked terribly hard—left early, came home late, I hardly ever saw him. He went along with my mother, who said, “No bicycle for him.” We could afford it. We had boarders who helped pay the rent, like Mr. Lichtenstein, who was a retired watchmaker. So it wasn’t the money.

But a bicycle? “You could fall!”

Roller skates? Well the hills in Williamsburg weren’t great, but there was an incline, and “You’d lose control and you’d be on Bedford Avenue and those buses . . .”

And playing marbles in the gutter, that wasn’t dangerous, but I’d be amongst the common ruffians. My parents were not educated, they were not rabbis, but they had a sense of themselves. I can’t think of the proper Yiddish word—doesn’t matter. You lived a fine and dignified life. And most of the people around us were noisy and sat outside on the stoops in their undershirts. So I couldn’t do those things.

As it turned out, I loved school. And though I was not the master of the streets, the second day I went to PS 122, I came home and said, “I will walk to school by myself.” Four blocks, two avenues, past the big armory to PS 122.

Going to school and coming back, the streets teemed with activity. Laundry delivered, big electric-driven trucks with chain drives, the bakeries, Dugan’s delivering rolls, the milk from Sheffield Farms on Heyward Street. I even remember horse-drawn carts. The Italian vegetable and fruit man came with an old nag, who was just two steps this side of the glue factory.

And then there were so many other people. There were street singers, and I remember the cutler, who ground knives. He would come peddling with a big stone wheel in front of him and a bell. He’d get to the middle of the block and hit the bell. All the mammas knew what the bell meant, and they came scurrying out of the houses with their aprons wrapped around scissors, knives, and the funny little chopping things that they used for “soul food”—chopped liver. You could hear the whirring, the screeching noise, and see the sparks as the stone whetted the metal.

So the streets were safe and full. Still, no bicycle. No roller skates. No scooter made of a stolen box, attached to old roller skates.

But the thing I craved most, because I loved books and reading, was a library card. The boarder taught me Hebrew when I was about two. I puzzled out the Yiddish paper once I figured out you read it from back to front. And we didn’t have much English in the house, but there were ketchup bottles.

I knew that the books were in this big, very elegant building with red brick, limestone, and marble, just a few blocks away, near Eastern District High School and the YMCA, the civic center of that part of Williamsburg.

But I couldn’t get my mother to walk me over and get the library card, ’cause anything involving public institutions reminded her of Brest-Litovsk in Poland, where every uniform meant danger, including the police, and every public office meant procrastination and insult and bribery and curses and humiliation. And of course walking that way also took you to the elevated train on Broadway—just a couple of blocks more—that took the men like my father across the Williamsburg Bridge into Manhattan to work, as many of them did, in the garment center. My father was a furrier.

So two things frightened her: the men’s world and the public world. And she wouldn’t do it.

But I came home from school one day, and I had the ultimate weapon:

“Teacher says.”

I listened to the teacher.

I said, “Mom, teacher says to get a library card.”

For some reason you had to show a gas bill. I guess they thought maybe you could forge rental receipts, and maybe electricity was not as widespread as I thought. Or maybe it was democratic—somebody who owned a house paid a gas bill as well as someone who rented. I don’t know.

But we took the gas bill over and found the appropriate desk. You had to be able to write your name or print it, and I was frightened because I never had the Spencerian copperplate hand that of course all the girls picked up. But with my tongue sticking out in concentration, I wrote my name, showed the gas bill, and got a temporary library card. Thirty days later, the permanent card came.

I don’t think I took out picture books. Because words were what I was interested in, and I would list them, and go over to the big dictionary and schlep the pages over, you know, looking for words.

My parents, in silent partnership with this great republic in which they had the most tenacious toehold, insecure in language and so much of American ways, had gotten me, in that unlaminated card, my ticket out of ghetto-mindedness. Unknowingly, somewhat unwillingly, they had given me a chance to satisfy my curiosity, such a powerful instinct for a lonely, lost, and rather sullen child.

And with it, in time, after Doctor Dolittle and the boys’ editions of Kipling and Stevenson and Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and, of course, Mark Twain—I haunted libraries—it was Dickens and Orwell and de Tocqueville. So that in time, and I’m proud of this, I’d achieved an independence of mind. And thanks to my humble self-extinguishing parents, enough of the independence of spirit that has to sustain independence of mind.

A line of poetry, which I’m not much given to, came to me. It’s a line of Shelley’s, and I think my parents would have loved it:

To hope and hope and hope till hope creates from its own wreck the thing it contemplates.

They did. We must.

—

Marvin Gelfand was a longtime New Yorker, born in Brooklyn. A product of the public schools of the city and the state of New York, he taught economics at the university level, was a literary editor at The Washington Post, freelanced as a book reviewer, and wrote speeches and orated for many, many worthy losing candidates. For years he lectured, consulted, and led walking tours about the history of the city of New York. He died in 2011, and we miss him.

Reprinted by permission of Hyperion Books, a division of Hachette Book Group.

ELLIE LEE

A Kind of Wisdom

There’s a kind of wisdom that fathers have, and then there’s the kind of wisdom that my father has. He thinks he’s totally brilliant, but I just think he’s crazy.

For example, when we first immigrated from Hong Kong, he thought it would be a good idea for all of us to have American names, which would make sense because it would make transition a lot easier. And so my dad chose as his American name “Ming” even though it’s not American or even his real Chinese name, it’s just another Chinese name—it’s a dynasty.

When we first came to America, we came to Boston. Being from Hong Kong, we had never experienced New England winters. We were penniless; we had very little money. My dad had the brilliant idea of making me my first winter coat, which he designed himself. He got this pink quilt material, which was totally inappropriate for a coat. The actual bodice of it floated away from my three-year-old body, so all the cold air could draft up. He didn’t have construction skills to make sleeves, so there were just these two slits in the front that I could use to grab things. It was this big pink bell. The design made no sense. But to this day he thinks it’s the best design.

Another example: one day he came home and there had been a sale on belts, and he’d bought a monogram belt, and he was so excited.

He was like, “Look at this!” and it had this big, shiny letter “A” on it, even though our family name is Lee.

And I was like, “Dad, why did you get a letter ‘A’ belt? That doesn’t make any sense.”

And he was like, “Oh, I got ‘A’ because ‘A’ is for ‘Ace.’ ”

You have to understand something about Chinese people. Chinese people are obsessed about being number one. Like, I have a belt now that says so. I’m number one! Ace! If you’ve never noticed, in Chinatowns across the country Chinese businesspeople always have to find the best “number one” name for their business in order to bring in money and good fortune, which is why everything is an “Imperial Dynasty,” “Lucky Dragon,” or “Number One Kitchen.”

That is my dad, that’s his mentality.

So in the first few years of being in this country, he had no time off and worked like crazy, and managed to save a little money to start up his own business. It was a very modest grocery store in Boston’s Chinatown. And of course he called it “Ming’s Market,” but in Chinese the name of it was

![]()

which literally means “bargain price market.”

And even as a little kid, I didn’t understand. He told me one day he would mark up something by just 5 cents, mark up another thing by 10 cents. I was like, “How are you ever gonna make money? This business model is insane.”

But you know, strangely enough, almost immediately he developed a really loyal following in Boston’s Chinatown, because for the first time working poor families actually had a place where they could buy affordable, healthy groceries, and eat well, which is no small thing when you’re poor.

So after about ten years he built it up to be a very successful business, and by 1989 he had moved into an enormous space—it became New England’s largest Asian market.

I was a snotty teenager. I still thought, “Well you’re still crazy. You’re a successful businessman, but you’re nuts. You have crazy ideas.”

So he’d been running his business on the first floor of this vacant building. It had been vacant for thirty years. And the landlord was trying to renovate the other floors to rent them out as retail space. But he was doing everything on the cheap, so instead of hiring a contractor, he was welding and renovating on his own without getting permits. And one day something got out of hand and this big fire broke out as he was welding. But it was OK, they evacuated the building—about 150 people—and the fire trucks arrived immediately and everything was fine.

Until the fire department hooked up their hoses to the hydrants and there was no water to fight the fire. And they were like, Huh, that’s weird. So they went down a couple of blocks and tried the next hydrant, and it was also totally dry.

What had happened was, a few months prior, the city of Boston had done road construction, and generally if they drill deep, they turn off the water pressure in case they hit a water main. And when they sealed up the road, they forgot to turn the pressure back up, so the firefighters had no tools to fight the fire.

It was a disaster. An hour later, the building was still on fire, and there was still no water. They were trying to jerry-rig something from a nearby hydrant, ten blocks away.

And as if things couldn’t get worse, the fire jumped an alley and the building next door caught on fire, and on the top floor were ten thousand square feet of illegally stashed fireworks.

Now firefighters couldn’t safely scale the ladders, and it was a surreal moment because things were exploding in celebration as my dad stood there, completely helpless, watching his life’s work being destroyed in a moment through no fault of his own.

So I got a call. I was a sophomore in college at the time, and I went out to his store the next day, when it was just smoldering; it wasn’t on fire anymore. And as I made my approach to the store, I remember seeing three elderly women, and they were crying.

I went up to them and said, “Is everything OK? Why are you crying?”

And one of the ladies looked at me, and then she looked at my dad’s burned-down store and pointed, and teary-eyed she said, “Where are we gonna go now that we don’t have a home?”

And that was a turning point for me. I hadn’t really thought about my dad’s store in that way. I just thought it was something he was doing to provide for the family, but in fact he was providing for a greater community. These elderly women, they didn’t have a community center to go to. They didn’t have a public park in Chinatown. This was the only place where they would actually run into their friends. And they spent a lot of time there. In a way it was like a second home.

I guess it is true. It sounds corny, but you do only realize what you have when you lose it.

So in the months that followed, I kept begging my dad for more stories. I asked him what he did with shoplifters, ’cause I was really curious.

And he said, “Well you know, one day I caught a kid shoplifting. He was only ten, and he didn’t know who I was. I was kinda following him around, and he was just taking stuff, stuffing it in his bag, putting it in his pockets. And at one moment he actually took a break from stealing and sat down and actually started eating the food he had stolen, right in the middle of an aisle.”

My dad told me that he came up to him, and he said, “Hey little boy, have you had enough to eat?”

And the little boy rubbed his belly, like almost, you know?

And my dad’s like, “Hey, so where are your parents?”

And the little boy said, “Well, um, they’re at work.”

My dad said, “Oh, well why aren’t you at home?”

The little boy’s like, “Because there’s no food at home.”

And my dad said, “Well you know, when you take stuff, especially if it’s at a store, and you don’t pay for it, it’s actually stealing.”

And the little boy got really nervous, like, This guy is gonna get me in trouble. And he was kind of angling for a way to get out.

But my dad said, “So in the future if you don’t have anything to eat at home, would you just come and find me and ask me for whatever you need? If you ask, I’ll give you whatever you want; just don’t steal, because stealing is wrong.” And in the months that followed I think my dad really looked forward to seeing the little boy.

It was these stories that I was craving, because in some way I think I was trying to re-create something that I had lost, taken for granted.

Whenever we went to Chinatown, lots of people would come up to us and say, “Please, we need a store like this again. When are you going to open up your store?”

And it was hard because my dad was basically penniless. The fire had caused about $20 million worth of damage, and he barely had enough insurance to cover it. So he really had no money. But he had this idea that maybe he could pool together what little money he did have with a lot of the original employees, people who were immigrants and had gotten their first jobs through my dad at the store. Some of them had been working there since the 1970s.

So they pooled together, and it was a big risk. The only location they could find was just on the outskirts of Chinatown, which in the early nineties, during the last recession, was like a no-man’s-land. It was so unsafe, and the only reason you would ever go there was to get a prostitute or drugs. And at the time I remember thinking, What’s the wisdom in that? Why are you going there? It’s so unsafe, no one’s gonna go, you’re gonna lose your life savings.

But he did it anyway because he’s crazy, and almost overnight the place was revitalized. There were really loyal people, families from the suburbs, who came and gave patronage to my dad. And people walked from Chinatown. Soon thereafter many businesses started popping up, and then there was more and more foot traffic, and then families started moving back into this neighborhood. And it was an amazing thing. He kind of helped revitalize this neighborhood, to the point that, fifteen years later, it became one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in Boston.

Which is why my dad got an eviction notice from the owner. He wanted to kick my dad out and knock down the whole block and build luxury condos.

At the time, my dad was seventy, and I said, “You know, Dad, what do you want to do? You have ninety employees, and they’re all in their forties and fifties. They don’t speak English. They’re very hard to employ. What’s gonna happen to them?”

And I remember my dad said, “You know, I’m seventy years old. I’m too old for this.

I’m too old to fight.”

And I understood. But I decided that I wasn’t too old to fight.

So I organized the community and led this grassroots movement to fight city hall and fight one of the largest developers in all of Boston. And at our first public hearing, there was a really amazing turnout, and we got enough press that even the mayor changed his tune and started supporting us.

And after the first initial hearing I went to the store, and when I walked in, there were these two older women who were my dad’s employees.

They rushed right up to me, and they said, “Thank you so much for what you did last night. You know, we normally don’t think that we have a voice, and we normally don’t think we can advocate for ourselves in that kind of way, so thank you for doing what you did.” And when I looked into their eyes, I saw so much compassion and humility and grace.

And it was at that moment that I understood the wisdom that my father had given me.

Ellie Lee is an award-winning director, writer, and producer of animated, fiction, and documentary films, which have screened at the Berlin Film Festival and over a hundred festivals worldwide. She is a five-time National Emmy Award nominee and won the 2009 Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award for excellence in broadcast journalism. She is a 2013 Sundance Institute Screenwriters Intensive Fellow and serves on the board of the nonprofit Karen Schmeer Film Editing Fellowship. Currently, she’s producing a new animated comedy Web series, Chinafornia.

Reprinted by permission of Hyperion Books, a division of Hachette Book Group.

Leave a Reply