“I am a man of struggle and my cinema is the cinema of the liberation struggle of my people.” -Yilmaz Güney

Critics are fond of separating a filmmaker’s “life” from his “work,” as if the two were related but autonomous spheres. In the case of Yilmaz Güney, the hollow-cheeked, mustachioed action movie star and director whose name has become legend in Turkey, it is clear to everyone that the two are inseparable. A communist Kurd, Güney was looked upon with an unfriendly eye by three successive military regimes in Turkey and spent twelve of his 26 years as a filmmaker behind bars.

Many of his films are set in prisons, and when they’re not, his characters are imprisoned by a variety of operations, such as the industrialization of Turkey’s countryside and the proletarianization of its rural nomadic tribes. Constantly hounded by the authorities for his communist “sympathies” while also hugely popular, Güney was a real threat that refused to be neutralized.

Having become an icon by appearing in seventy to eighty films in the 1960s—mostly bloody low-budget revenge movies, shot within days and often based on popular Hollywood movies like ONE-EYED JACKS and I DIED A THOUSAND TIMES— Güney had developed a considerable following by the time he started directing his own films. As critic Atilla Dorsay has said, “His films are watched with as much attention and ‘respect’ as a religious ceremony. The audience is humiliated with him, suffers with him, and when, finally, he decides to revolt, they approve with applause and shouts of joy.” When he turned to analyzing class injustice in HOPE (Umut) in 1970, it was a major shift in affective register. Whereas Güney’s character in THE BRIDE OF THE EARTH from two years previously was a mix of the Man with No Name, Antonio das Mortes, and the T-1000, a near-indestructible vigilante who follows only the law of the gun, his character in HOPE is more like Antonio from BICYCLE THIEVES. What the physician-pedagogue in Truffaut’s THE WILD CHILD says about the boy savage applies equally to this transformation in Güney’s on-screen persona: “What he’ll lose in strength he’ll gain in sensitivity.”

HOPE is considered a landmark in the history of Turkish cinema. Güney called it an “epic of verité” due to its break with the conventions of Turkish commercial cinema, the gleaming sets and powdered starlets typical of Yesilcam (the Turkish Hollywood). Although it is often compared to De Sica’s BICYCLE THIEVES, HOPE also has much in common with Glauber Rocha’s BLACK GOD, WHITE DEVIL—with its rural merchant protagonist who gets fleeced one too many times and turns to a messianic preacher for guidance—and with Ousmane Sembene’s BOROM SARRET, the tale of a poor horse-cart driver in Dakar getting kicked around by the law.

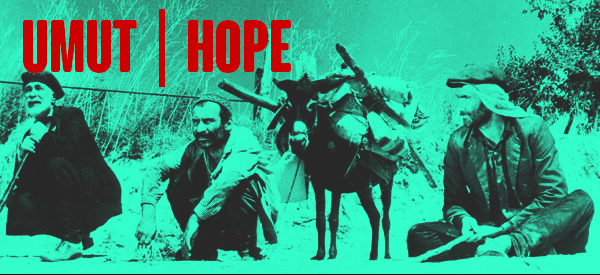

HOPE a.k.a. Umut

Dir. Yilmaz Güney, 1970

Turkey, 100 min.

In Turkish with new English subtitles by Spectacle

Thurs June 19

7:30pm at Spectacle Theatre

124 So. 3rd Street Williamsburg

http://www.spectacletheater.com/yilmaz-guney-the-indomitable-south-part-1/#hope

Leave a Reply