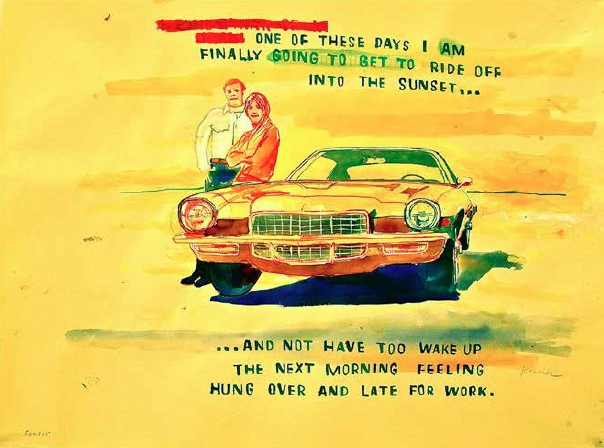

“Car at Sunset” (ink on paper) 2012, by David Kramer.

By David Kramer

When I was a young artist back in school, I remember telling friends that I didn’t trust the work of young artists. I was an admirer of so many artists whose careers seemed to blossom in the second or even the third phase of their lives. I remember specifically singling out the careers of certain heroes as prime examples of greatness coming through the long haul of perseverance.

I embraced the careers of certain heroes to fortify my theory, and even though I was just a twenty-something-year old kid at the time, I was in this thing for the long haul, and perhaps already buffering myself for the long slog ahead. I took great interest at the time in the career of Willem de Kooning. De Kooning, who did not have his first solo show until he was in his forties, hit the ground running. Not only did de Kooning take sole possession of the role of THE guy in painting (after his sluggish start), but later in his career he went on to do so much more; that’s what excited me the most about him. After his historic run of abstract expressionism, he returned to the figure and later back to abstraction; he never seemed to settle on anything in his endless pursuit of painting. There is of course the rumor that the paintings were still wet when they came to pick them up to drive them over to the gallery for that first show. And, of course, there’s the rumor that the work for this historic and epic show might not ever have been finished had it not been for the fact that the invitations were already in the mail when the truckers showed up. He would probably still be working on those paintings.

I remember reading somewhere a list of years of peak performance that was organized by profession. Careers like Chess Champion and Concert Violinist were low on the chart. You reached the height of your career at 8 years old. Tennis players were about 14 at their height. Basketball players were 24. Doctors were in their late 30s, architects in their 50s.

And, way down at the bottom of this list, were sculptors and painters. Their years of peak performance were, astonishingly, in their 70s. This was sort of a voila! moment for me. I embraced this shaky list and set my sights squarely on the horizon. While I have had many successes in my Art Career, failure is by far winning the race to the finish line, and I dare say that’s the case for the careers of most artists. Let’s face it, even the most successful artist is doomed to be disappointed. The cliché that you won’t really hit your stride as an artist until you are dead didn’t just come out of thin air. Everyone knows that is when your career really takes off.

When I was in school, I was a terrible student. I am dyslexic, and learning to spell and read and multiply made getting through school impossible. In the days of typewriters, before computers, I would hand in illegible papers covered in Whiteout (ask your mother what that is), and I would get them back with failing grades, and often with no grades at all. There were just notes written across the top saying things like “CANNOT READ!” To survive this utter embarrassment, I developed a very refined and calloused thick skin, and a distinct mistrust of teachers, school, and authority to boot. Never mind that along with my dyslexia came perhaps a severe case of ADD. I blamed my teachers for their unsympathetic response to my lousy test scores.

Back in the day, the only exceptions to my distain for teachers were the art teachers. They seemed to be the only ones who ever gave me any support and encouragement, and, most importantly, good grades. If it had not been for getting A grades in art class, I most certainly would not have gotten into any college, or even graduate school. My grade point average was embarrassing, and when it came time to take the SAT, most of the points I earned came from spelling my name correctly.

At some point while in college it occurred to me to focus my studies solely on art. It was a knee jerk reaction, I admit. I had miserable grades in economics and history and psychology, but once I had a drawing teacher who gave me a C-. This one shitty grade (which would have been totally acceptable in any other subject) really seemed to change my whole world forever, and set me on the path I am now on. I went to ask that teacher about my grade. I was by my estimation the best artist in my class, and I showed up for every class eager to work. Why was my grade so bad? Well it turned out I had forgotten that we had taken an anatomy test in the class earlier in the semester, where we were to memorize and spell correctly all of the muscles and bones in the human body. My spelling had been so atrocious; I basically scored in single digits. My professor told me, “… there were people in the class who didn’t even speak English, and they spelled more things right than you had!” Never mind that these bones and muscles all had Latin names. I got his point. This guy went on to tell me that I had an A+ ability to draw, and an F attitude, which in his book translated into a C- grade.

I did not bother to argue with him, but I left his office, dropped all my classes outside the Art Department, and proceeded to devote myself to being an artist—one with an attitude. I was not going to let this teacher get the best of me. A year and a half later, after I graduated, I returned to the school to participate in an alumni show … my painting hung right next to his on the wall. And mine was so much better.

Defiance seems to me to be the main ingredient for good artwork and great artists. And I’d like to add a few more ingredients to my list of what is necessary to cook up a truly good artist. A good artist needs to be delusional, a good liar, and able to bullshit not only his audience, but also himself, into total submission. For me, every time I hit the proverbial bump in the road, I keep telling myself I haven’t hit my stride yet (“…I’ll show you, motherfucker!”). And a good artist needs time.

After I left college, I went on to get a masters degree. Despite my hatred of school, I knew I needed something more than what I got out of my undergraduate degree. I enrolled at Pratt Institute in the fall of 1985.

(If I sound old … well that’s a good thing, right?)

While finishing my thesis I had gained a lot of support from many of the faculty members. There were opportunities and introductions that came out of school, and some gallery shows. I remember thinking to myself that as much as I liked the attention, I was still making work that had a certain amount of baggage from my teachers. I wanted to be lost and to experiment. I wanted to find my own voice. I was young and naïve, and I knew it. I didn’t like art produced by young artists who had little or no life experience to go on. And I certainly wasn’t excluding myself from this sentiment.

Over the next few years I spent time in and out of New York, getting to do residency programs or creating some sort of firewall around me when I was here. Gallery shows were not high on my list of things to do at the time. I wanted to find out more about what it was I wanted to make. I experimented with performance and even open mikes; I made some films and wrote all along while making paintings and sculptures. All of which, somehow, I feel are ingredients in the work that I am now producing, almost thirty years later. I kept my nose to the grindstone, making lots of work and continuing to set my sights on a rosy future.

The Art World has changed. Art on the whole has changed. The world has changed. Post-modernism has been totally consumed by the Computer Age. Information is so accessible and easy to come by; it is now in theory simple to conceive of an idea, find out everything you need to know about it, and find someone who can produce it faster and cheaper than you ever could have imagined. And they will ship it to your door before you wake up the next morning.

The idea that one has to struggle and suffer, in the model that I had built my whole career around, now seems somehow old fashioned and stupid.

Recently I was in Los Angeles. I was with some friends, and we went to openings in Culver City. There was a gallery show where an artist had built a plywood room on an incline and had ropes attached to the walls. The walls were covered in green paint, and outside of this room were projected videos, which were shot earlier, of some guys hanging from these ropes and pouring green paint all over themselves and the walls of this room. I was chatting up a woman at the opening whom I’d just met, and I said, “… This work seems just like Paul McCarthy’s.” To which she replied, “… Of course it does. He studied with him!”

The message was clear: this guy is cool because he got a show. Paul McCarthy is cool and should be revered. Paul McCarthy approved of his student’s work because it confirmed to Paul McCarthy that his work was awesome and should go down in history because people are mimicking what he does. And me, I am a jerk for being stupid enough to state the obvious. Needless to say, my high-minded ideas about art were a real bummer and a conversation stopper. I could hear clearly from the back of this woman’s mind, in her L.A. accent, “… Duh! Who’s the old guy?”

Looking back now, maybe it is time to reexamine my long-term goals. I am right between my twenty-something ideals about art and my goal age for peak performance at seventy, and I have to admit that maybe I have been a little misguided in my strategy. As much as I spent the last 25 years of my art career relying on clichés like “slow and steady wins the race,” now other clichés float through my brain, like “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks” or “past performance is the strongest indicator of future result.” These play with a steady drumbeat. You might call my current view something of a mid-life crisis, but I’d rather not go there.

This morning I spent an hour on Google looking for this list that I once quoted about peak performance years for various careers, and I couldn’t find it. All that kept coming up was peak performance training for athletes and young professionals. As I said, this is a different age, and times they are a changing. And if I can’t find, on a search engine, this list that I’ve been basing my entire career on up until this point, and I am not living in China, then maybe I’ve been a little too delusional for a little too long. That’s okay. I am still young enough to learn a few new tricks. The way I see it, I better find my own peak performance soon, or I am not going to be around to see 70 and whatever benefits might be waiting for me if I should ever get there. All of the life-experience-gaining moments that I craved so much as a kid have certainly been taking a toll on me.

David Kramer is a New York-based artist. Recent shows include Hi-Life at Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris (spring 2014) and Malibu on the Mediterranean at Galerie Tanit, Beirut, Lebanon (Fall 2013). He is also a contributing writer for the NY Times Opinionator blog.

Leave a Reply