Reprinted from the collection of essays A Case for Identity by Philip Gould (Boson Books Press, 2013)

JULY 2012 — An exhibition of drawings by Ellsworth Kelly opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art two weeks ago. I found the show a profoundly moving experience. Take note that the exhibit is tucked away in the American Paintings Wing making its whereabouts difficult to find. I might have thought the setting was an oversight or an unintended offense but on further reflection I could agree with the curator’s decision as completely in sync with the character of the works. Most of the drawings are done with pencil (graphite) on white paper.

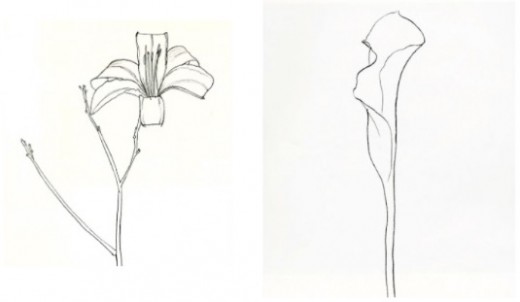

Plant Drawings by Ellsworth Kelly.

They are contour drawings of vegetal subjects like leaves or stalks or flowers. I should say, rather, semi contour drawings because the artist allowed himself the latitude to lift his pencil and to replace it wherever it made sense to complete a given objective. The means were so simple but the effects so complex. Compositional devices might be a stem or a twig with leaves attached to the right and to the left, much as you would expect them to be in nature. In the drawing, however, the distribution of forms had less to do with the nature’s process than the decision-making of the artist. Every shape and placement was determined by its contribution to the composition as a whole. And the intervention of the artist in every mark is perceived by the viewer and in the process establishes an intimate rapport between the two.

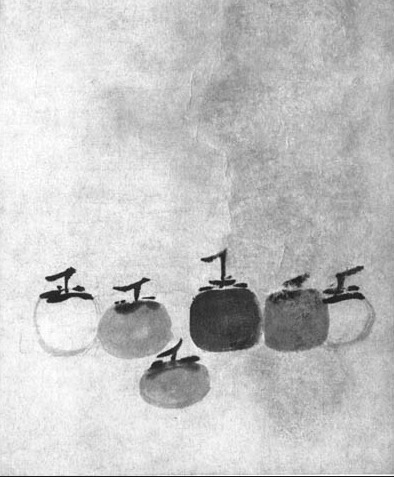

In my study of Chinese painting I came across the colophon “No Brush, No Ink” by which I understood that the painting referenced by the enigmatic expression arrived without the intervention of the artist, just came into existence by itself. This was the Ch’an (Zen) approach, for art should be spontaneous and appear effortless. One of my favorite Chinese artists is Mu-Ch’i (c.1200-70) who painted a hanging scroll called “Six Persimmons.” The painting has no foreground, no background, and no chiaroscuro, that is, no shading of light and dark and no source of light and finally no color, it is monochromatic. The painting is created with brush strokes alone. None of the strokes are repeated; an extraordinary achievement of combining complexity and simplicity. Kelly has gone a step further by his drawings which have no strokes, only lines. His drawing of a heap of apples measures up to Mu-Ch’I for its meager means and fullness.

“Six Persimmons” by Mu-Ch’I.

When you stand in the middle of any of the four galleries devoted to Ellsworth’s drawings you cannot really see the works. The effect is as though standing in a billowy cloud. The point here is that you need to view his works at close range. Intimacy is required and in that stance you sense a communion with an artist of a particular sensibility: modest and subtle which explains why the somewhat remote location of the Kelly drawings seemed to fit the character of the artist. As far as I know this was the first major exhibition of his drawings even though he was working on them all his life. Like artists in the Orient, Kelly will accept his claim late as he is in his mid-eighties.

Not too long ago The Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted another of my much-admired American artists Richard Serra who could easily stand as a counter-point to Ellsworth Kelly. Serra’s works were as big and bold and black as Kelly’s are nuanced and reserved and mostly white. Drawing after drawing by Serra were filled with a powerfully assertive black mass and one wall in the museum was dedicated to an in-situ painting from floor to ceiling as a great vertical rectangle of black. These two American artists are as divergent as one can imagine and both offer us distinct aesthetic personalities.

Leave a Reply